When we talk about “innovation” in government tech, what do we mean?

During a recent project, 18F partnered with a government innovation lab to help them understand the impact innovation can have at their organization. During this engagement, 18F surveyed multiple digital innovation groups in cultural heritage institutions and federal agencies on this very question.

As an innovation group ourselves, the results both challenged us and strengthened our confidence in the importance of trying new approaches in the government space. Through our research, we identified:

- How these groups define innovation

- Common challenges faced by innovation groups

- Strategies these groups use to experiment in the federal space

Defining innovation

Throughout our research, we asked interviewees to define innovation and took note of how they described experimentation within their organizations. Definitions of innovation we heard included:

- “Novelty plus change”

- “Taking a calculated risk”

- “An investment in learning”

- “Leveraging the best knowledge and expertise in the org”

- “Trying a bunch of things and discarding the stuff that doesn’t work”

- “Non-linear”

- “Having an open mind”

Although innovation is often paired with the word digital, none of the definitions we heard are specific to digital innovations or technology at all! We learned to define innovation as looking for new ways to approach familiar situations.

What innovation looks like

Innovation isn’t always a formal process and can be called by other names. It may manifest as experimentation, learning, creative solutioning, and trying new approaches. Above all else, innovation takes place in an environment where it’s safe and easy to try new things. Innovation and human-centered design (HCD) go hand-in-hand to validate early ideas quickly with direct feedback and involvement from end users and affected communities.

What we learned from interviews also raised a strong counterpoint to the belief that innovation is inherently risky. Our research indicated that more mature external innovation labs use experimentation as a way to de-risk and future-focus their work. In other words, they found that success comes from experimenting, getting feedback, and adapting from lessons learned. Often the cost of doing nothing is greater than the cost of being wrong because there’s an opportunity cost to simply continuing with the status quo.

Common challenges facing innovation labs and how they can be overcome

Lack of leadership support

Groups who are charged to innovate within their larger organizations need the trust of their agency leadership to make any meaningful progress. Groups who don’t have leadership cover must work much harder for a fraction of the return. For example, these teams experience the challenges of:

- Justifying their existence and funding

- Working within the context of shifting priorities that are outside of their control

- Lacking the authority to make decisions within their domain

Earning full support from leadership is important for the success of the lab, but building that takes time and persistence. As one research participant put it:

“You have to pay the dues, you have to earn trust from leadership before you can make your own decisions. You have to show them you can use resources in the best way possible.”

Successful innovation labs have found ways to improve leadership cover by having direct communication channels and access to people who can sign off quickly on decisions. To get leaders’ buy-in and support, these groups keep leadership updated on their activities and connect the possible outcomes of experimentation to the goals of the organization. Supportive leaders have accepted the short-term risks of experimentation, and go above and beyond to celebrate successes and communicate them outside of the agency. For specific examples on what this looks like in practice, see the 18F blog post series called “Senior executives are the allies tech teams need.”

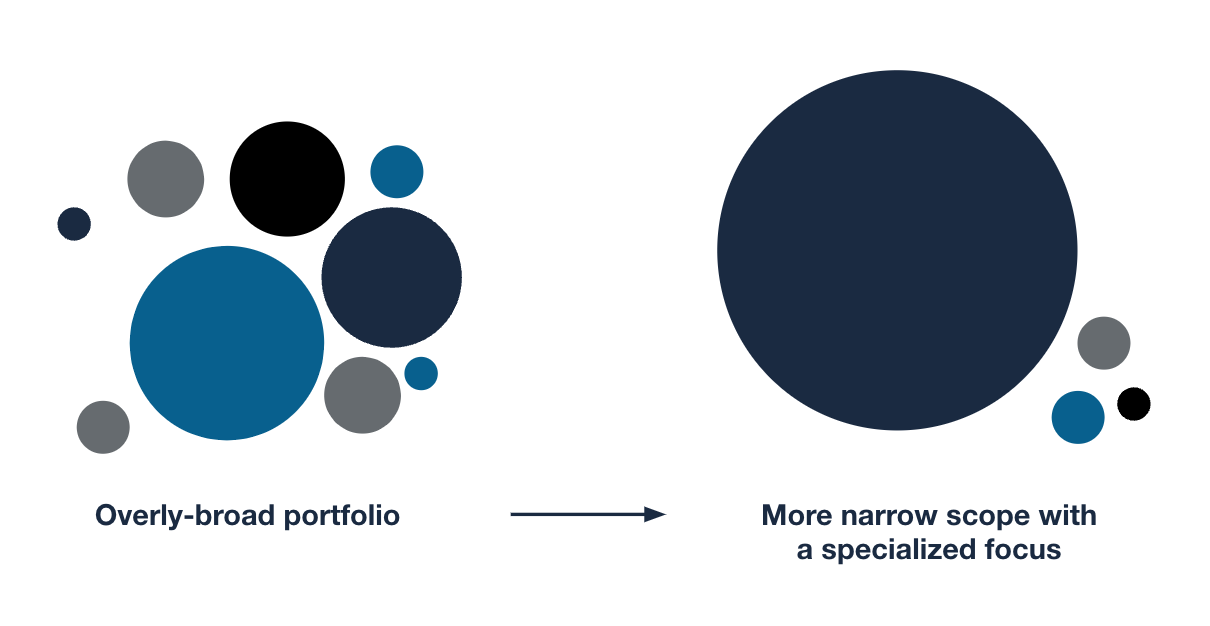

Too broad of a scope

Some innovation labs are treated as a catch-all for any work that’s seen as modern or leading-edge. We found it’s important for these groups to narrow the scope of their portfolios. A representative from an innovation lab shared with us:

“Innovation is a big word and it means so many things, you can’t do all of them … Being one innovation lab that does all the things will inevitably be a failure.”

Innovation groups with a broad scope encounter several challenges:

- Staff are stretched thin working on multiple opportunities

- Lack of time to develop skills, knowledge, and relationships in particular areas

- Difficulty explaining to others their value proposition and mission

Groups we spoke to are working through this challenge by building a brand around a particular specialization, method, or platform. For example, an innovation group might choose to focus on human-centered design, or running challenges that bring in industry partners.

Regardless of what they decided to specialize in, something we heard echoed several times was: “you’ll only be able to deliver value if you pick something that lets you focus enough to deliver and be successful.”

Moving from experimentation to delivery without adequate support

Many of the innovation groups we spoke to do not support long-term products. This is due to the nature of their work — they must avoid permanent commitments of staff and resources in order to be flexible and quickly take on new activities. This means that any tangible products resulting from experimentation need to find a home outside of the innovation group. One person we spoke to told us:

“We don’t run services ourselves. Once projects reach a level of maturity or we think there’s value for the org, we want to hand it off to another team to manage … it’s a much longer process to try to state that into formal adoption.”

Experimentation outcomes that are being handed off to a new production home are at risk of failure if the receiving team is not adequately prepared to provide the necessary support. Multiple innovation groups who had experienced this problem explained how they minimize this risk:

- Only pursue ideas with an interested potential long-term owner

- Collaborate with the team who will ultimately host any outcomes throughout the experimentation process

- Slowly shift the responsibility and ownership of experimentation and iteration to the long-term owners

Identify eventual homes for final products early on. This establishes implicit stakeholder buy-in and provides a place for the product to land. The sooner in the experimentation pipeline this happens, the better, because it frees up the limited bandwidth on the innovation groups to focus on the next thing.

Difficult to quantify success

Across the board, people we spoke to want to improve how they measure their impact. Metrics that prove the value of a program are particularly valuable to innovation groups, who will have failures along with their successes when trying things out. Although groups were able to measure project-specific metrics, like number of experiments and time required for tasks, it was much harder to capture the impact of innovation from a short-term lens. “It’s very easy to measure success through numbers and kind of miss it still,” one group told us.

Skillsharing, innovation work, and relationship-building take time, and it can be hard to justify the value you’re providing with quantitative metrics alone. Innovation groups focus on telling stories about what they’ve learned, and where the future is taking them. These narratives are critical to communicating the impact of innovation in government.

The impact an individual innovation lab can have is exponential when they take time to publicize their successes. Working in the open allows others to learn from a lab’s processes and lessons, and can give others the tools to try new approaches within their own teams. For example, these stories can be shared out through documentation, workshops, toolkits, presentations, blog posts, and case studies.

Relationships and skillsharing have the power to spread innovation

The above challenges are specific to individual innovation groups, but these groups exist to meet the challenges that their larger organizations face. Beyond trying to find solutions to problems themselves, we learned that innovation groups are also focused on teaching the rest of their organization how to innovate. They do this through building relationships across silos and sharing skills with colleagues.

Building relationships

Building a network of trusted relationships across an organization is key to creating consensus for future technological change. Creating spaces for conversation may not seem like innovation, but it ensures that future technological change has the buy-in of a diverse set of stakeholders. This approach treats relationship-building as the work of creating lasting organizational change.

When the focus of innovation is only on creating new technology, the necessary work of building the internal relationships that are needed to implement new ideas is sacrificed. The most successful labs focus not only on building things but also act as organizational conveners that create space for conversation across multiple interests in and around their organization.

How innovation groups share skills

Nearly all of the innovation labs we talked to have developed some sort of training as part of their service, either for staff in their own organization or for other organizations. This went by many names: training, upskilling, skillsharing, capacity-building, guiding, and teaching.

Whatever they called it, innovation groups all recognized that:

- Their innovation efforts would be marginal at best unless they could bring the larger organization along with them

- Individual departments are the closest to the organization’s audience and users, and the pipeline of innovative ideas begins there

- Bringing others early into project ideation and prototyping increases trust and buy-in for a project, and eases project hand-off from lab to department

Skillsharing is a direct path to cultivating an innovation mindset across the organization and is a way for labs to create lasting change. As one innovation lab put it:

“We want to get to the point where we can influence the entire agency … for better results. Maybe we won’t be needed anymore because inherently the whole agency is innovative.”