If you work in the federal government and want to deliver custom web applications, you will almost certainly need to go through an Authority to Operate (ATO) compliance process. An ATO is an authorization approved by an Authorizing Official (AO) who accepts a system’s security risk. We say “ATO process” as shorthand. The process generally includes a series of steps to categorize, prepare, implement, assess, authorize, and monitor a system to ensure it meets an acceptable level of security – and that the system complies with the many laws and regulations applicable to federal information technology.

ATO processes work differently at different federal agencies. As a technology and design consultancy inside the United States government, 18F has worked on ATOs at many of them. We are still learning and experimenting, but there are definite patterns we have seen work well across multiple agencies.

Since there are already great guides for describing the steps involved in an ATO process, in this post, we will focus more on the attitudes, approaches, and strategies that we have found useful.

In order to successfully work with security compliance teams to ship software in government, we:

- Architect systems anticipating the ATO process

- Stay curious through a complex process

- Find a meeting point between different ways of doing things

- Embrace the great parts

- Start early to deliver early

- Build in time to focus on the ATO

- Scope to de-risk

- Embrace DevOps, continuous integration, and automated testing, while staying flexible on format

- Maintain documentation alongside source code

Architect systems anticipating the ATO process

As you explore the requirements of your system, consider selecting an architectural foundation that allows you to inherit as many of the NIST 800-53 controls as possible from an existing provider or product. This can dramatically reduce the scope of work required for the ATO, reduce timelines, and improve overall system security.

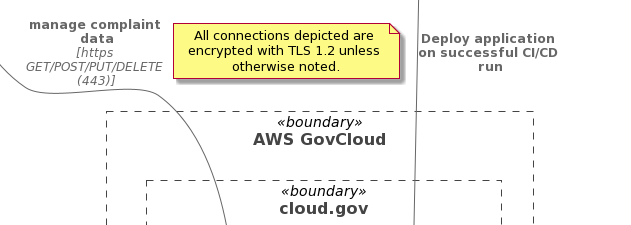

Architectural decisions could include targeting a FedRAMP Cloud Service Provider (CSP) instead of an existing agency data center. Or, if you are already using a cloud platform, choosing between Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) resources, or a Platform as a Service (PaaS) or Function as a Service (FaaS) approach.

Finally, evaluate shared services within the federal government — such as login.gov, api.data.gov, cloud.gov – as well as the approved and procured services within your agency to avoid unnecessarily building a program-specific implementation.

Stay curious through a complex process

When starting on any new ATO process, ask lots of questions. Your security compliance partners will likely assign your project an Information System Security Officer (ISSO) to guide you through the process. Invite your ISSO to your system design meetings and sprint demos to avoid surprises later in the process. Seeking out other people and teams who have successfully navigated ATO processes within the agency is also a good idea.

At the beginning of the process, you may want to ask your ISSO questions like these:

- “What ATO packages may we see as examples?”

- “What do development teams usually miss during the ATO process?”

- “As an ISSO, what role do you like to play on the projects you assist?”

- “What does the timeline for this process look like? What are the key checkpoints or milestones that we should be aware of?”

As you go through the process, we’ve found it helpful to ask the question “what is the underlying goal of Meeting X, Process Y, or Document Z?” Asking about purpose helps the team understand the core goals of the process, and opens up new ways to meet those goals.

Find a meeting point between different ways of doing things

Teams that are steeped in agile approaches and methodologies might experience some culture shock when they embark on an ATO process. Many security compliance processes take a more traditional waterfall approach. To get an ATO, you may need to find ways to combine an agile development process with waterfall-style meetings at points along the development process.

Embrace the great parts

The ATO process is not just a paperwork exercise — it offers benefits to your team and the software you are delivering. For example, the ATO process strongly emphasizes documentation. Great software development teams also strongly emphasize documentation. At times the amount of documentation required by your security compliance process might feel overwhelming. It might be helpful to think of this process as a “forcing function” that will emphasize and strengthen the team’s ability to deliver documentation.

The ATO also helps you secure your web application by guiding you through steps and reminding you about procedures. Have you worked through a disaster preparation exercise recently? Are your scans as complete as they ought to be? Do you have a plan to restore your database quickly if something happens to it? The ATO will prompt you to consider an array of scenarios and concerns that will help make your web application better.

Start early to deliver early

As soon as you know that your software project will need an ATO, get started on the process! Security compliance teams appreciate an early heads-up about projects coming down the pipeline. The sooner you start the process, the sooner you can finish it and the sooner you can launch production software that will be valuable to your users. When you start, ask your security team for the list of controls you will be responsible for, after taking into account controls that can be inherited from your cloud environment and agency processes. Then, have the tech lead review the substance of those controls to inform the ongoing sprint plans. Reading the controls directly in the NIST guidance is a good idea. The GSA FedRAMP program also produced useful materials that can help guide your tech lead.

Build in time to focus on the ATO

The ATO process can take a surprising amount of time and energy, even when things are going well. You will be juggling working on your system, creating documentation, collaborating with others, communicating with your ISSO, and iterating through the process to respond to feedback. The time required for your ATO may vary; a FISMA Moderate system will need more attention than a FISMA Low system. Regardless, it’s a good idea to plan ahead for a lot of time in case you need it. Talk with your ISSO early about checkpoints and deadlines so you can work towards meeting them.

Scope to de-risk

Cut initial scope down to a minimum reviewable size. A minimum reviewable size will have all the core components in place that the security compliance team will need to review, which will likely include:

- Choices about the tech stack: What coding language(s) will you use? What software tools will you use to build your system?

- System architecture: What are the different parts and pieces of your system? What external systems will it connect with?

- Security controls: These will generally include user management, access controls, audit logging, and other key functionality related to security and compliance.

- Core functionality: What initial set of features will allow your team to test key assumptions and begin the ATO process? This question is a big one, and could easily be the topic of its own blog post. A product manager might want to use the concept of a minimum viable product here. If your product is technically complex, with a high number of external integrations and API connections required, your tech lead may want to use the concept of a “walking skeleton”: a tiny initial implementation of the system that performs a small end-to-end function, while linking together all the main architectural components.

You can still make changes and keep building and improving your system after its initial ATO. Further changes and functionality may flow through Agile and DevOps processes (or through a Change Control Board, in a waterfall environment). You may need to seek a new or modified ATO if or when you find that your system will need to change in major ways — for example, if you need a new system architecture or need to connect to a new external system.

Embrace DevOps, continuous integration, and automated testing, while staying flexible on format

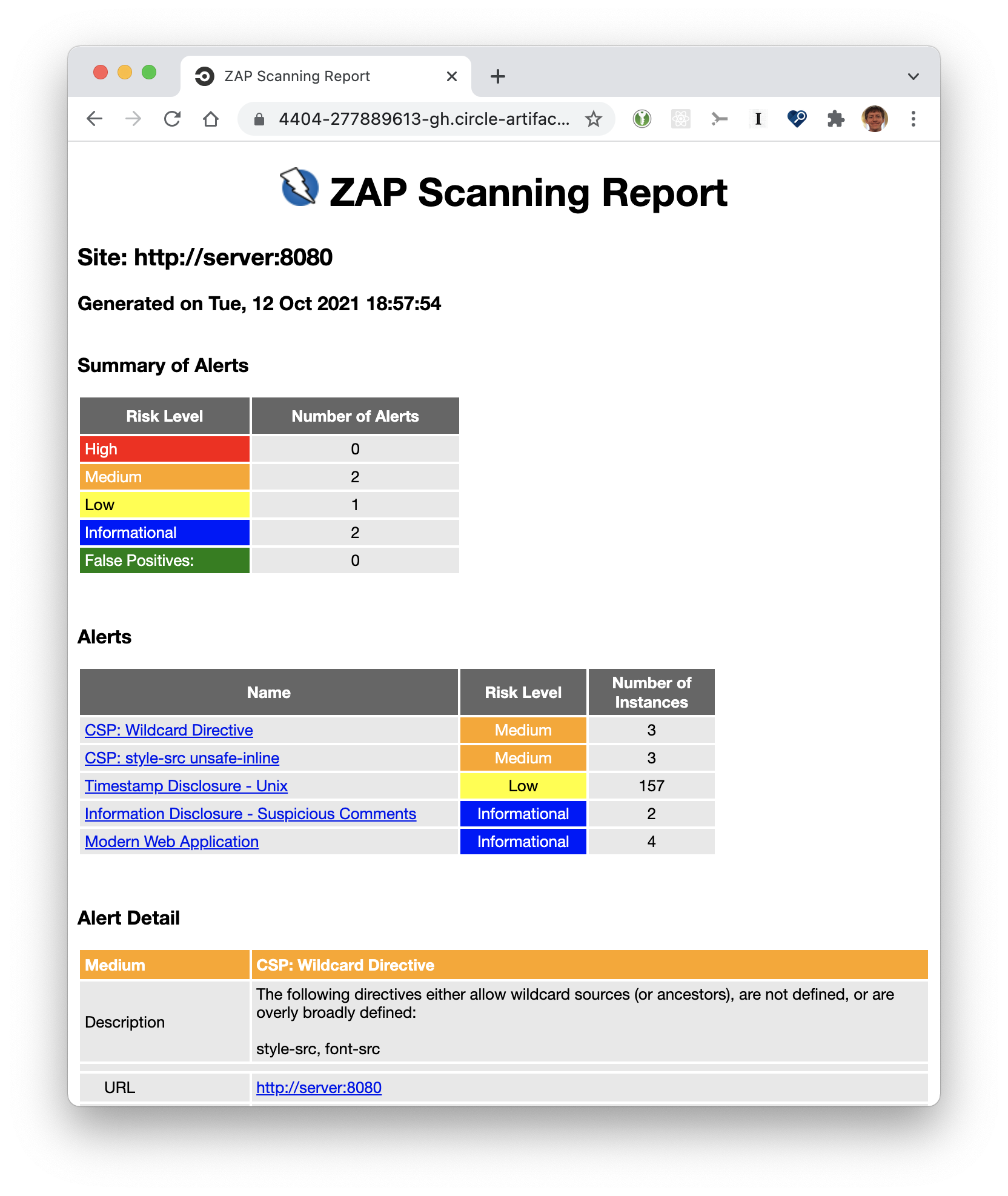

DevOps, continuous integration, automated testing, automated security scanning using open-source tools such as OWASP ZAP: all of these modern software development practices show your team’s commitment to rigorous testing of your system. Take the time to walk through the practices your team is employing, and show how these techniques test and verify the security of your system. If your development team is running a full suite of automated tests for correctness, security, and accessibility on every proposed code change, make sure your security compliance team knows this is happening and sees the benefits. You may need to be flexible on the format you use to share information about the testing you are doing. Taking the time to put results into a familiar format like Word, PDF, or an HTML page can go a long way.

Maintain documentation alongside source code

Very frequently, ATO documentation is authored solely for the purposes of the compliance process and then is reviewed, approved, and archived – not to see the light of day until the next review or reauthorization, a year or more later.

To break down this knowledge silo and keep security documentation evergreen, we recommend that you maintain ATO artifacts alongside the system’s source code. The System Security Plan (SSP) is particularly applicable to this approach, since its diagrams, tables, and narratives are derived from your system’s source code, configuration, and Infrastructure-as-Code. Using this approach, the development team can update these living documents when they make significant changes to the system and use them during product development and onboarding of new team members. They become the single source of truth.

There are other potential benefits as well. If you maintain security documentation throughout the development cycle, future reauthorization processes will be easier. And we believe that when these docs are maintained out of the security silo, the whole product team can better understand the full context in which the system is being evaluated, operated, and maintained, so they can build a better product.

Of course, there are nuances to this approach, especially if you embrace open source development, as we do at 18F. The code for our projects can usually be public, and so can a great deal of documentation. Notable exceptions would include the system’s Plan of Action & Milestones (POA&M) (your security “TODO” list), certain vulnerability scanning tool results, and possibly other artifacts that aren’t derived from the open source code. Please work closely with your security team in these circumstances to understand what you might be able to document in the open.

As one excellent example of doing security and compliance work in the open, our sibling organization cloud.gov published their configuration management approach, contingency plan, and incident response checklist. Working in this way has benefits to the entire ecosystem, since other projects can learn and benefit from the security and compliance work done by cloud.gov. At the ecosystem level, we are also optimistically tracking efforts like OSCAL, which are building standardized formats and tools to ease ATO compliance work.

Happy trails, and good luck!