This is the second in a two-part series exploring the basics of running a remote moderated usability test. In part one, we explored usability testing at a high level: what it is and why it’s important. In this post we’ll review a five-step process for conducting your first round of tests:

- Choosing what to test

- Planning for research

- Recruiting users and informing their consent

- Running the sessions (we recommend three sessions at 45 minutes each)

- Discussing and sharing the results

This process roughly approximates how 18F routinely conducts usability tests in close collaboration with our agency partners.

Step 1: Choose what to test

The rule of thumb is to test earlier than you think; it’s better to test a sketch, wireframe, or prototype with one person early than to evaluate your production website with 20 people. As designer Erika Hall says “The most expensive [usability testing] of all is the kind your customers do for you after launch by way of customer service.”

If you’re working on a totally brand new design and have nothing to share yet, consider testing tools your users might otherwise be familiar with, like a legacy system or a “competitor’s website” — that is, a website that’s analogous to the one you might build. All you need is something that’s shareable that communicates how you want to help users accomplish their goals.

Step 2: Plan for research

Planning for research can sometimes feel like a project unto itself, but it shouldn’t. (For a particularly harrowing story as to why you shouldn’t over-plan research, see the beginning of this Medium post.) The truth is, when it comes to running your very first set of usability tests, the hardest part is choosing what to test.

Next, you’ll need to work with your team to confirm:

- The timeline

- What you hope to learn

- What you’ll ask participants to do

- Which of your users should participate

- Who will moderate

- Who will observe

Hold a 90-minute planning meeting and invite anyone who has an interest in what you’re testing (if you don’t know who that is, conduct stakeholder interviews). Use your discretion of course, but try and invite at least one person who has the ability to directly impact the design of the product or service you’re testing; this might be a program manager, a contracting officer, or even an agency attorney since government digital services are often manifestations of agency policies.

At the start of the meeting, remind everyone why you want to run a usability test (to ensure design quality and better understand user expectations), and ask the group what they hope to learn: what are the riskiest design decisions the group wants to inform (more pointedly, what are the riskiest assumptions you want to challenge)? Ask the group what user-centered metrics they’ll use to determine whether or not the concept “passes” the test. For example, “we expect users to complete their work in under 5 minutes, with no errors.”

Next, manage the team’s expectations around how long testing will take. We recommend budgeting two weeks from start to finish for your first round of tests. Each test itself will take about an hour, and you’ll only need to do three tests to find things you’ll want to fix. The “extra time” helps ensure that whomever is leading the research — presumably you, dear reader — can thoroughly attend to the logistics that usability testing requires.

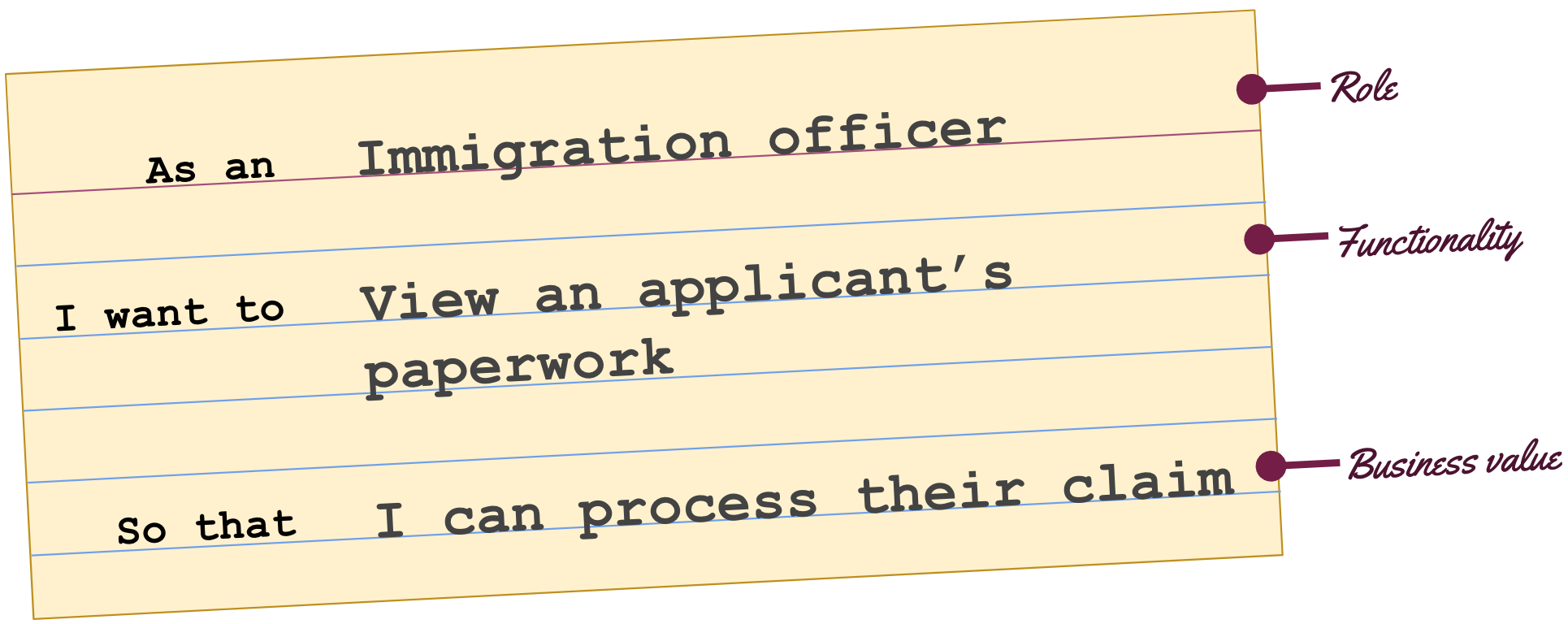

Next, identify the tasks you’ll use to frame the test. If you’ve already made personas, journey maps, or user stories you’re in luck; these artifacts contain user tasks. If you haven’t made any of those things, don’t fret. Ask the group to name and rank “the most essential things that users need to do” (in relation to what you’ve chosen to test), and then pick the top two or three.

Next, collaboratively author a brief, believable, relatable scenario for each of your top tasks. The idea is to get your users in the right headspace during the test. For example, if we were testing GSA’s intranet we might present participants with the following scenario:

Imagine you’re working on a new web application that will help individual employees at 18F identify and plan to attend conferences together. Someone on your team says that because your application collects personally identifiable information you might need to complete a privacy impact assessment. Using GSA’s intranet, show me how you would identify whether or not your system will require completing a privacy impact assessment.

Once you’ve got your scenarios, incorporate them into the script you’ll use to moderate the tests. Here’s the boilerplate script we use at 18F (place the scenarios under the “tasks” heading).

Next, identify your participants, or the users who should participate in this round of tests. It’s important to identify people who will find your scenarios believable, but don’t unnecessarily limit yourself to people you’re already familiar with; recruiting provides an incredible opportunity to invite diverse feedback and perspectives into the design process (for example, when was the last time you solicited feedback from people who use screen readers).

Finally, decide as a group who will moderate and who will observe the usability tests. Good moderation requires a mix of sociability, self-awareness, and listening skills. Don’t let just anyone moderate; be honest about whether or not moderation will be difficult for someone (for example, the product owner may find this difficult). If it’s the moderator’s first time, do a practice run to ensure the moderator is comfortable taking on this role.

Step 3: Recruit users and inform their consent

Once you’ve identified who should participate, you’ll need to create what’s known as a recruiter (also known as a screener) to invite those people’s participation. At its core, a recruiter is simply a call-to-action for potential research participants. Many recruiters include a short form to collect information to further filter participants, but an email address is all you really need — which, if collected on its own, isn’t subject to PRA.

Meet with your agency privacy office to confirm the language you’ll need to include on the Privacy Act Statement accompanying your recruiter (here’s GSA’s Privacy Act Statement for Design Research), and to discuss how you’ll store and manage the information you collect. Once your privacy office gives the okay, share the recruiter on listservs, social media, or even a popup on your website (which we prefer). For example, a social media-based recruiter could just say

“Help us improve the design of OPM.gov! Sign up to participate in a remote usability test by emailing participate-18F@gsa.gov. Learn more about how we’ll protect your information at https://www.gsa.gov/reference/gsa-privacy-program/privacy-act-statement-for-design-research”

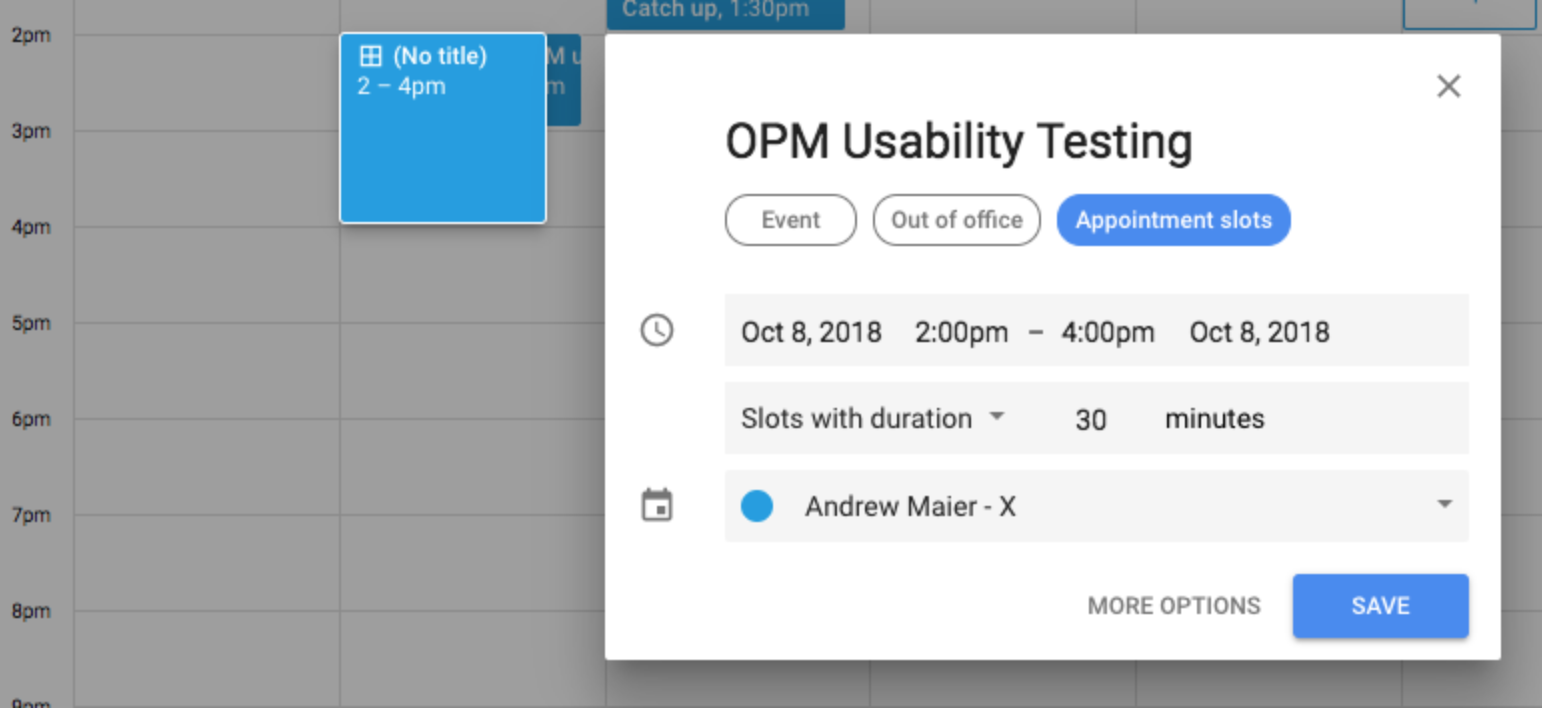

Give potential participants a couple of days to respond to the recruiter. In the interim, block off time on the calendars of those who elected to observe the test. We suggest using 60-minute appointment slots for each 30-to-45-minute test (to account for pre- and post-interview rituals). Block off three hours for three tests.

Once you’ve heard from potential participants, reply to a handful of them — one at a time, of course — to more fully explain what participation will require. Pass along a link to book time on your calendar, and give each potential participant a day or two to respond. (If you still have an empty appointment slot after 48 hours, reach out to another handful of people. Give that group a day or two to respond. Repeat until you’ve either exhausted your list of potential participants or filled your three appointment slots.) Here’s an example email:

Hi there,

My name’s Andrew. I'm working with OPM to incorporate feedback into our design process. I’m reaching out to confirm your interest in participating in a usability test.

Do you have any time in the next week to share your thoughts? We'll only need about 45 minutes. During the test, we’ll ask you to share your screen and accomplish some tasks using a design concept. If that works for you, please book an appointment with our team at the following link: [Calendar appointment link]

Thanks,

AndrewPS: If you do not wish to participate in this test, please ignore this email. If you do not wish to be contacted for any future test related to my work, please reply to this email requesting to be removed from my contact list.

Next, prepare a participant agreement (GSA provides research participants with agreements to explain the nature of its studies and to explain at a high level the privacy implications of participating in agency-led design research). Whenever a potential participant makes an appointment, thank them and pass along a copy of the agreement to begin the informed consent process. Answer any questions the participant has and collect a signed agreement before proceeding.

Step 4: Run the sessions

On the day of the test, pass along to each scheduled participant any links or files that they will need to participate. This is also a good time to reiterate any logistics that their participation will require, such as screen sharing: “Here’s a link to the site we’ll ask you to use later today while sharing your screen:[link]”.

Usability tests often follow key moments: introductions, warm-up, tasks/scenarios, follow-up, and wrap-up. Give the moderator time to review the script beforehand (and potentially this interview checklist) and make a copy of the script for capturing notes during the test. We prefer to name the copies of our scripts “participant #”, where # is the number of the session, in an effort to protect participant privacy.

If your observers have access to a collaborative document-editing tool, invite them to the “participant #” document to take notes during the session. Observers should keep their notes as verbatim as possible (in other words, avoid interpreting what people are saying or doing at this point), and include timestamps every so often to help with analysis later.

Before the test, confirm that anything you’re testing works as you expect, and that you’re able to record the test (assuming your participant consents to recording during the test itself).

During the test, the moderator should verbally confirm with the participant that it’s okay to record the session (it’s okay if you are not allowed record, but if that’s the case your observers will need to take detailed notes), and assure the participant that there are no wrong answers and that they should to think out loud. Otherwise, the moderator should follow the script and remain silent. Before the participant shares their screen, the moderator should remind the participant to hide any windows they don’t want recorded. If the participant gets frustrated or asks for help, the moderator should reply “how would you expect this to work,” or “what would you do if I weren’t here?”

For their part, observers should mute their microphone, pay close attention to how users are accomplishing tasks (especially along the user-centered metrics from step two), and optionally contribute to a rolling issues log.

Immediately after each session, engage everyone who attended the test — except the participant, of course — in a post-interview debrief. Here are the prompts we use. Get everyone on a call to note what went well and what went poorly, and to decide if there’s anything that should change before the next test.

Step 5: Discuss and share the results

Many first-time researchers do not budget enough time to analyze and synthesize the results of their research. Don’t do this. Plan to spend a day or two after your research to first emotionally and later intellectually process what you’ve heard.

Immediately after the tests conclude, pass around to your colleagues, especially those who weren’t able to join the tests, links to your most informative recordings with relevant timestamps. This will give your colleagues a chance to draw their own conclusions before the synthesis meeting, and should help you get everyone on board with research findings.

Once your colleagues have had a chance to consider the data itself, schedule a 90-minute synthesis meeting to review any/all of the following:

-

Session highlights, especially

- Patterns you saw

- Differences between what users say and what they actually did

- Workarounds — times users accomplished tasks in unexpected ways

- Anything else you noticed

-

Task completion rates, and whether or not users met your success criteria

-

Issues from your rolling issues log

-

Any questions concerning user needs that these tests raised (ending with more well-informed questions is better than ending with user interface tweaks alone; while the latter is valuable in the short term, the former can align your team in solving the difficult problems that will leave users happier in the long run)

Conclude the meeting by determining how the team will use what it learned in service of future design decisions (as usability.gov says “for a usability test to have any value, you must use what you learn to improve the site”). For example, if your team kept a rolling issues log, you might conclude the meeting by prioritizing those issues relative to (1) the business value of tasks they inhibited completion of, or (2) the frequency with which users encountered them. Once you’ve prioritized the issues, get them into your product backlog.

After the meeting, you’re done! Write a brief summary documenting what you did, what you learned, and any decisions your team made. Delete any recordings from the sessions to further protect the privacy of your participants (and be sure to ask that anyone you shared recordings with to do the same).

That’s all folks

We hope this series provides everything you need to get started conducting your very first round of usability tests. If you have any questions or comments, don’t hesitate to reach out to us at 18f-research@gsa.gov.

Finally, we (Sarah and Andrew, who co-authored this series) would like to to take a moment to celebrate a few of the offices and civil servants that helped make this blog post-series possible. We’d like to thank:

- Amirah Aziz in GSA’s Office of the Chief Data Officer, who recently organized and ran GSA’s 2018 Data Summit, which provided a great forum for internal knowledge sharing;

- Anahita Reilly, Matthew Ford, and Sheev Dave in GSA’s Office of Customer Experience for encouraging us to present on 18F’s approach to usability testing;

- Aviva Oskow and Emmanuel Pressley in Andrew’s critique group for providing feedback on our initial presentation;

- Amy Ashida, Julia Lindpaintner, Victor Udoewa, and Ben Peterson in GSA’s Research Guild for helping to draft many of the templates (such as the interview checklist) referenced in this post; and

- Marcela Souaya and Richard Speidel in the GSA Privacy Office for reviewing the information provided in this series.