Emileigh is a content designer at 18F, and Christine is a content strategist who works with the Government Digital Service (GDS) in the UK. They met for the first time on a sweltering summer day in D.C. A quick cup of (iced) coffee turned into a months-long, transatlantic conversation on the different ways writers can test online content to see whether it needs improving. This post was first published on the GDS blog.

Much like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s famous saying, we know good content when we see it.

Good web content is clear. It’s actionable. Readers find what they’re looking for — and they’re looking for a lot these days. People rely on websites to conduct research, fill out tax forms, read the news.

We know good content when we see it, and we’re frustrated when we don’t.

Keeping this in mind, are there ways that writers can quantify and measure their writing? We’ve looked at different tests you can run depending on the age of your audience. Finding appropriate ways to test our content helps us improve and find best practice patterns for creating copy.

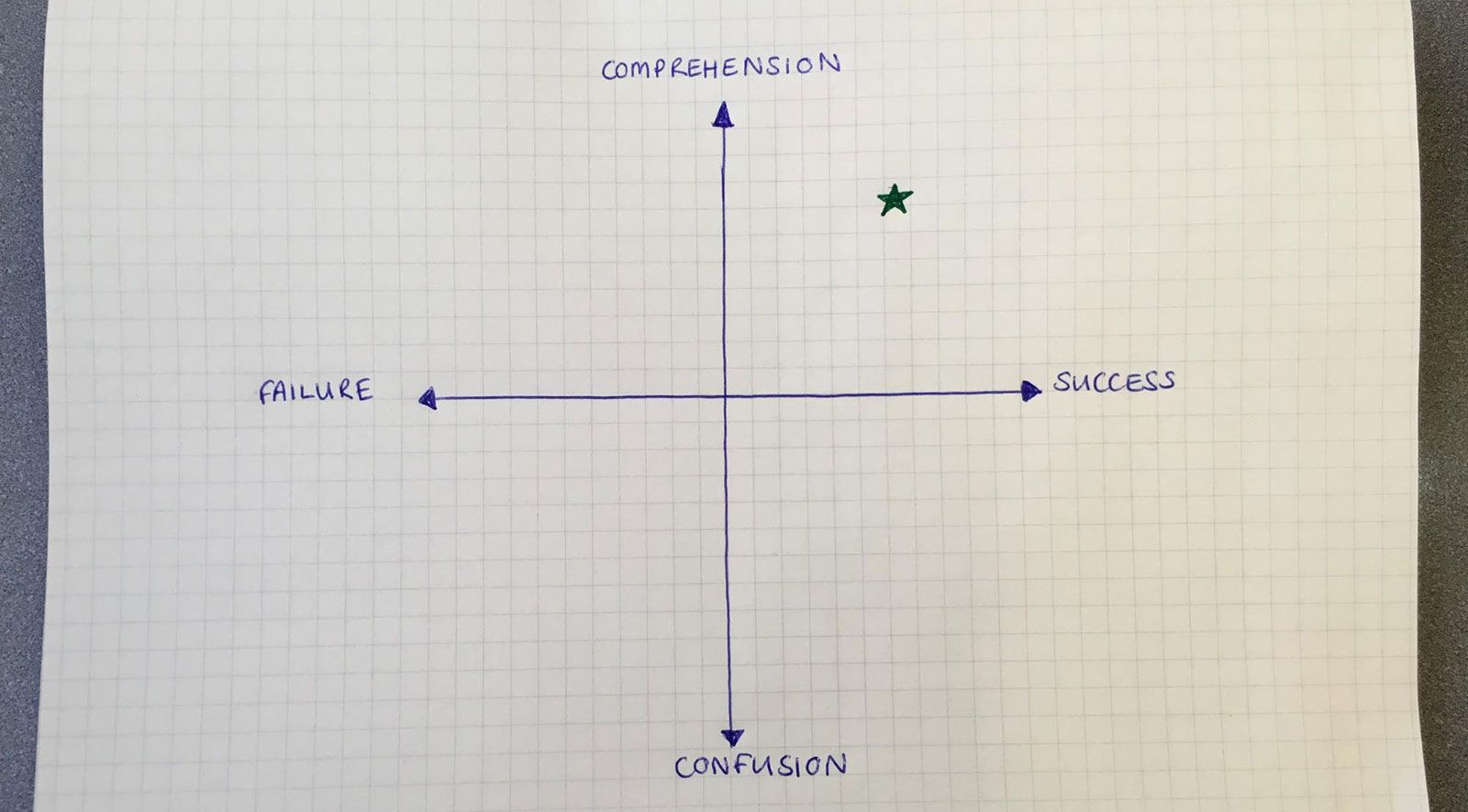

*Christine’s graph of good content. The star marks

the sweet spot.*

*Christine’s graph of good content. The star marks

the sweet spot.*

Who you are writing for

Readers will come to your content with varying levels of knowledge and education. Tell knowledgeable users what they know, and you’ll bore them. Assume they know more than they do, and you’ll frustrate (or lose) them. Whenever possible, keep things simple, short, and clear.

Here’s a good rule: If you’d like to reach a broad range of users, you should strive to write at a middle-school level. A 2003 Department of Education assessment showed average Americans read at a seventh–eighth grade level.

Testing your content depends on your audience

When it comes to seeing if the content you’ve written is working, the way you test it will depend on who you’ve written it for. We need to pay particular attention to how we frame our usability sessions, because of the stress associated with taking a “test.” It’s the content that’s being tested (not the person), but this distinction needs to be made clear.

Open-ended questions

Asking open-ended questions — for example, “What does this mean to you?” — is helpful when creating content for people with different cognitive needs. Maybe they have learning difficulties or aren’t familiar with the language. Additionally, if you’re writing content for children, using open-ended questions is a good way to see if they understand the information.

Using open-ended and task-orientated content questions allowed the Every Kid in a Park project to keep pressure low and still measure how well kids understood the website. For example, one question we asked was, “How would you use this website to sign up for Every Kid in a Park?”

The Every Kid in a Park homepage reads at a 4.5 grade level and was

tested with kids through the University of Maryland’s HCI lab.

The Every Kid in a Park homepage reads at a 4.5 grade level and was

tested with kids through the University of Maryland’s HCI lab.

Let people choose their own words

When you ask people to self-identifying language, you allow them to have a direct influence on the copy. This technique can be useful for sensitive content. For example, GOV.UK has content on what to do after someone dies, not after someone “passes away.”

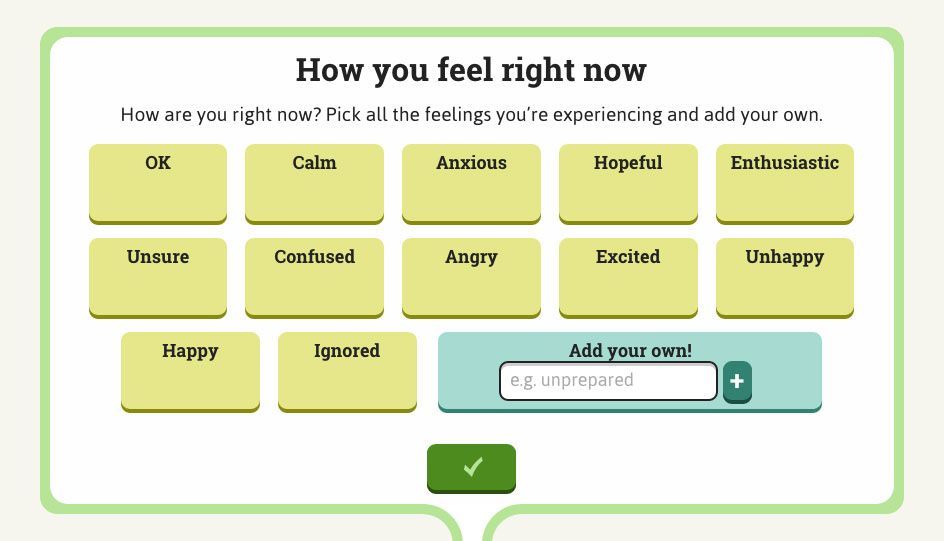

Christine recently worked on an app that helps young people using social care services prepare for meetings. The app aims to help them talk about their feelings; they can choose the feelings that they’re experiencing, plus add their own.

In testing, target users were asked to list all the feelings they’d experienced in the previous two weeks. The feelings listed by users in testing were matched to the ones already in the app — plus the feelings people had written into the “add your own” field.

The goal was to test whether the feelings chosen for the app were representative and appropriate.

A/B testing

This kind of testing compares two versions of content to see which performs better. It’s a good way to test how users connect with your content. Maybe your site is easy to read and understand, but users aren’t interacting with it in the way you hoped.

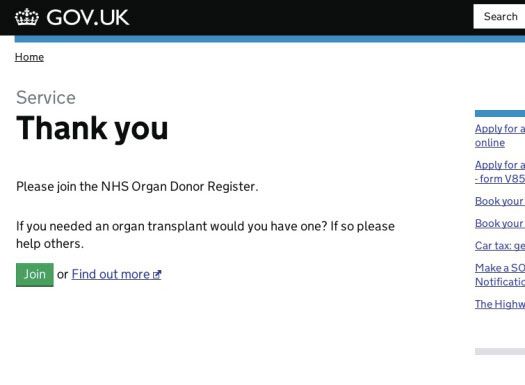

The organ donation sign-up case study shows how A/B testing works. Because this message appears after booking a driving test, we know users will be over 17 years old.

The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) wrote eight variations of content asking users to sign up as organ donors. For example:

- Please join the NHS Organ Donor Register.

- Please join the NHS Organ Donor Register. Three people die every day because there are not enough organ donors.

- Please join the NHS Organ Donor Register. You could save or transform up to 9 lives as an organ donor.

The sign-up rate for each piece of content was measured and the most successful was:

)

)

Each content variant the NHS tested used plain language and could be easily understood. The A/B test showed which call to action was most effective (though not why).

Cloze testing

For content about technical subjects — like finance, regulation and health — the Cloze test is ideal to help measure your readers’ comprehension..

In the Cloze test, participants look at a selection of text with certain words removed. Then they fill in the blanks. You look at their fill-in-the-blank answers to see how accurate they are to the original text.

When creating a Cloze test, you can delete words using a formula (every fifth word), or you can delete selectively (key words). You can accept only exact answers, or you can accept synonyms. Sampling as many readers as possible will give you better accuracy in your results.

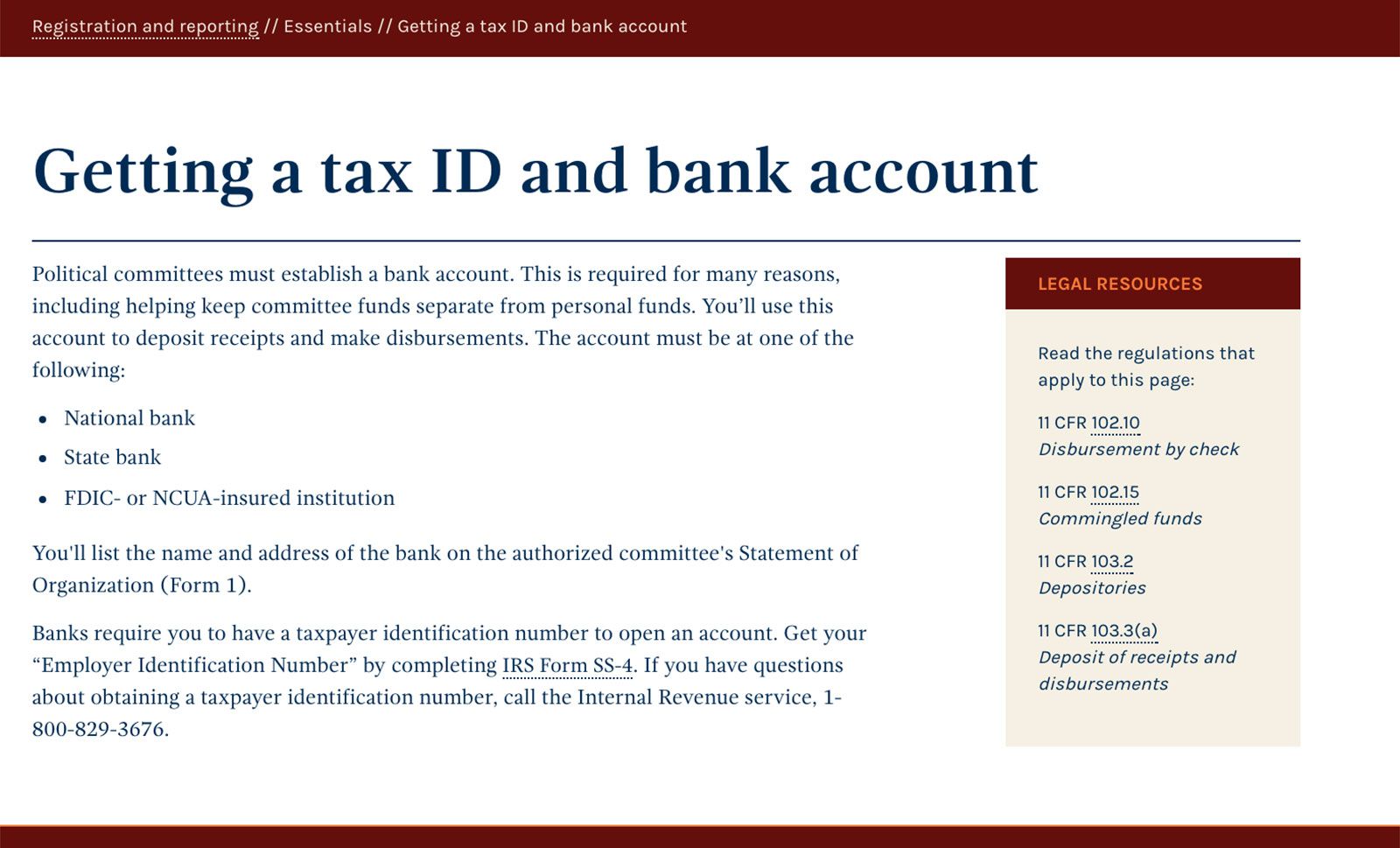

When developing Cloze tests for betaFEC — the Federal Election Commission’s new web presence — Emileigh created Cloze tests from passages of 150 words or more. She deleted every fifth word, and she accepted synonyms as answers. She was hoping to get test scores of 50 percent or greater accuracy; in practice, FEC’s Cloze test scores ranged from 65 percent to 98 percent, even better than she hoped.

*This page from [beta.FEC.gov](https://beta.fec.gov) is one of several tested using a Cloze

test.*

*This page from [beta.FEC.gov](https://beta.fec.gov) is one of several tested using a Cloze

test.*

Preference testing

Christopher Trudeau, professor at Thomas M. Cooley Law School in Michigan, did research into legal communication to find out ‘to what degree do clients and potential clients prefer plain language over traditional legal language’. He found that the more complex the issue, the greater the reader’s preference for plain English and that the more educated the person, the more specialist their knowledge, the greater their preference is for plain English.

He employed a range of ways to test content for his research, including A/B testing and asking respondents:

“Would you prefer this or this version”

then following up with:

“Why / why not?”

He then asked longer, qualitative question series:

“Have you ever read a document that was difficult to understand?”

“Did you persevere?”

“Why did you stop reading it?”

He named the method of using a mixture of A/B then qualitative questions “preference testing.”

For checking whether people understand risks (in informed consent cases) he says the best way to check comprehension is for the person who has read the document to be asked follow-up questions, for example, “Based on what you read in the document, can you explain the main risks to me...”

This means a real person — not a computer — uses their judgment to assess whether they understood the content.

Measuring what you’ve written

Over time, organizations have developed reading scores and indexes for measuring the “readability” of content. For example, the Coleman-Liau index, the SMOG index, and the Gunning fog index.

One that we find consistently suits our needs is the Flesch-Kincaid grade level. Developed for the U.S. Navy, Flesch-Kincaid measures sentence and word length. The more words in a sentence (and the more syllables in those words), the higher the grade level.

Using these formulas will help you quickly estimate how difficult your text is. It’s a clear metric that can help you advocate for plain language. But, like every formula, Flesch-Kincaid misses the magic and unpredictable nature of human interaction.

They also can’t help you figure out that “patience you must have my young padawan,” is harder to read than “You must have patience, my young padawan.”

We’d love to hear about your ways of testing content and comprehension. Reach out to us on Twitter @18F, or by email.

Further reading

GDS’s research team put together tips for testing your words when doing research.

A List Apart has a useful blog post on testing content.