Conventional wisdom often encourages engineers to start with a big architectural overview. Services with databases are connected via lines and arrows to other services. Caching layers, load balancers, and other complex shapes are wedged into the flow of information. For tech savvy people, these diagrams give some comfort that performance and security are addressed. Non-tech people can point to the diagram with some comfort that very smart people are doing very complex things.

Architectural plans provide comfort to everyone because they look like a plan. The way forward is for the engineers to fill in servers and infrastructure, making the map real.

Unfortunately, this kind of a grand plan usually leads to technical-debt that collapses towards complete immobility. Complexities in even one of these services can take down the entire project. Unknown problems at the beginning can't be rolled into the new plan easily because all services are dependent on this architectural contract.

In short, architectural plans push the team towards waterfall development, a system that has fallen out of favor as more and more projects have failed.

How can we avoid architectural handcuffs?

“Design” is an ambiguous word in the software world. On the one hand, “design” is used to describe the graphical user experience. On the other hand, engineering software “design” is the process of building small, modular components that are decoupled. Both of these types of design are essential for freeing a project from impending technical debt brought on by an architecture-first plan. Here are some ways that focusing on user experience design and software design can help your project avoid technical debt.

Starting from user stories and user experience

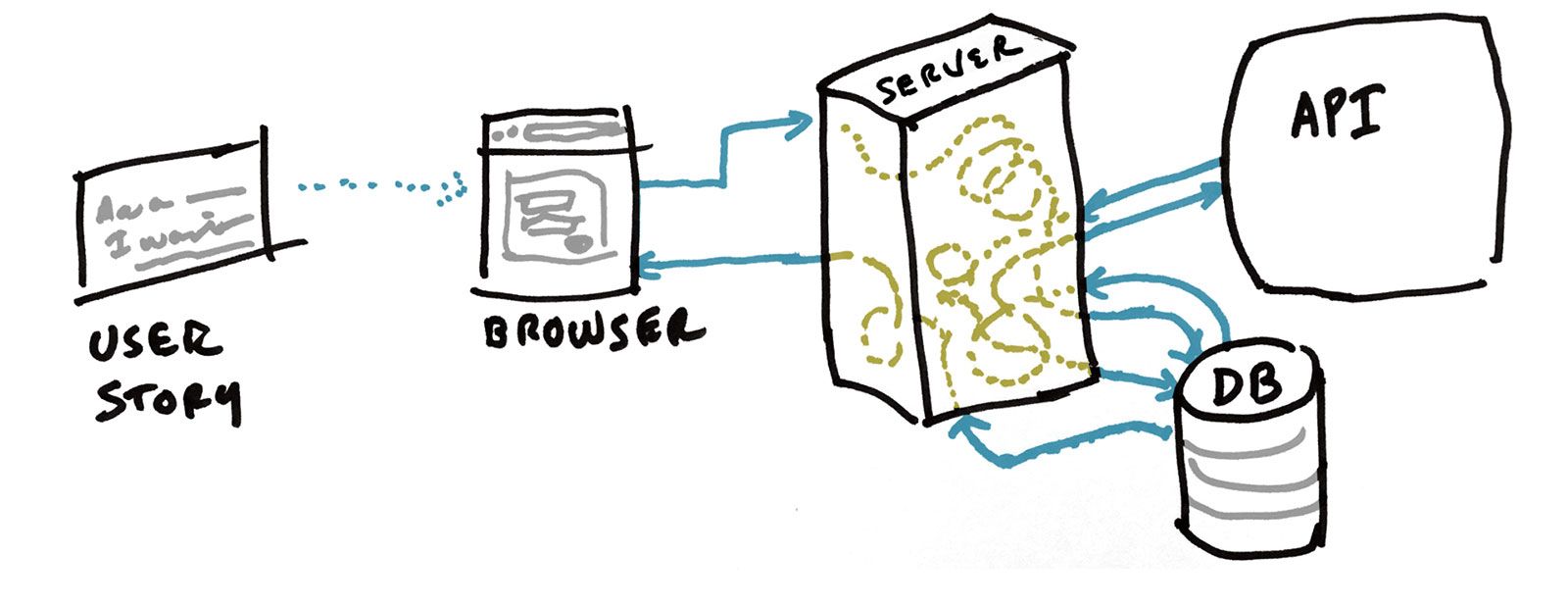

*A user story generating architecture organically.*

*A user story generating architecture organically.*

User stories are simple scenarios told from the point of view of a person using the software. There can be many types of users for an application. For example, an application might have people consuming the application via a public web page and others who are developers consuming it via an API. The application may also need administrators to establish content or permissions.

Formats for a user story are pretty simple:

As a user of some kind, I want to see or do something, so that some benefit is had.

In this story, you would fill in the bold sections with a user type, a goal, and benefit. An application should start with tiny scenarios like this that build functionality for each user. It’s the job of the product or project manager to write these stories and prioritize them.

Often teams are used to thinking in terms of architectural plans, and the stories they have in mind are far too big. Instead of thinking of one scenario for one user they are imagining the whole. This is an example of a story that is too big and architecturally focused:

As a website consumer, I want to be able to see all the publicly available information

so that I will be informed about the services available.

A better first story would be something like this:

As a website consumer,

I want to be able to see a homepage with the agency logo

so that I know I am at the right place

For teams used to thinking of architecture, this will seem like an impossibly small story. Because it’s the first story, it will still involve a lot of effort for the engineering team:

- Build a web application with a homepage and logo.

- Setup a staging server to make that website available to the product manager.

- Create a production server and devops procedures for migrating from staging to production.

Subsequent stories will not require this much setup. A good second story for an agency might be this:

As a website consumer,

I want to be able to see a list of projects

so that I know what is happening in the agency.

With the infrastructure in place, this story will roll out much faster. In this fictitious project stories might roll out like this:

- As a website consumer, I want to see a page dedicated to each project in the projects list, in order to see more details about the project.

- As a website consumer, I want to be able to navigate between project details pages and the project list, in order to move between important information quickly and easily.

Having finished a small set of stories about projects at the agency, the product person might decide that the most important priority is showing employee profiles so that the public can reach the people they need. They would build out a cluster of small stories to accomplish all the related goals.

After the team addresses lots of stories, driven by their top priorities, the architecture will have evolved on its own. That can be pretty dangerous if not also kept in check via the other side of the design process, software design.

Keeping our code from becoming a structureless mess

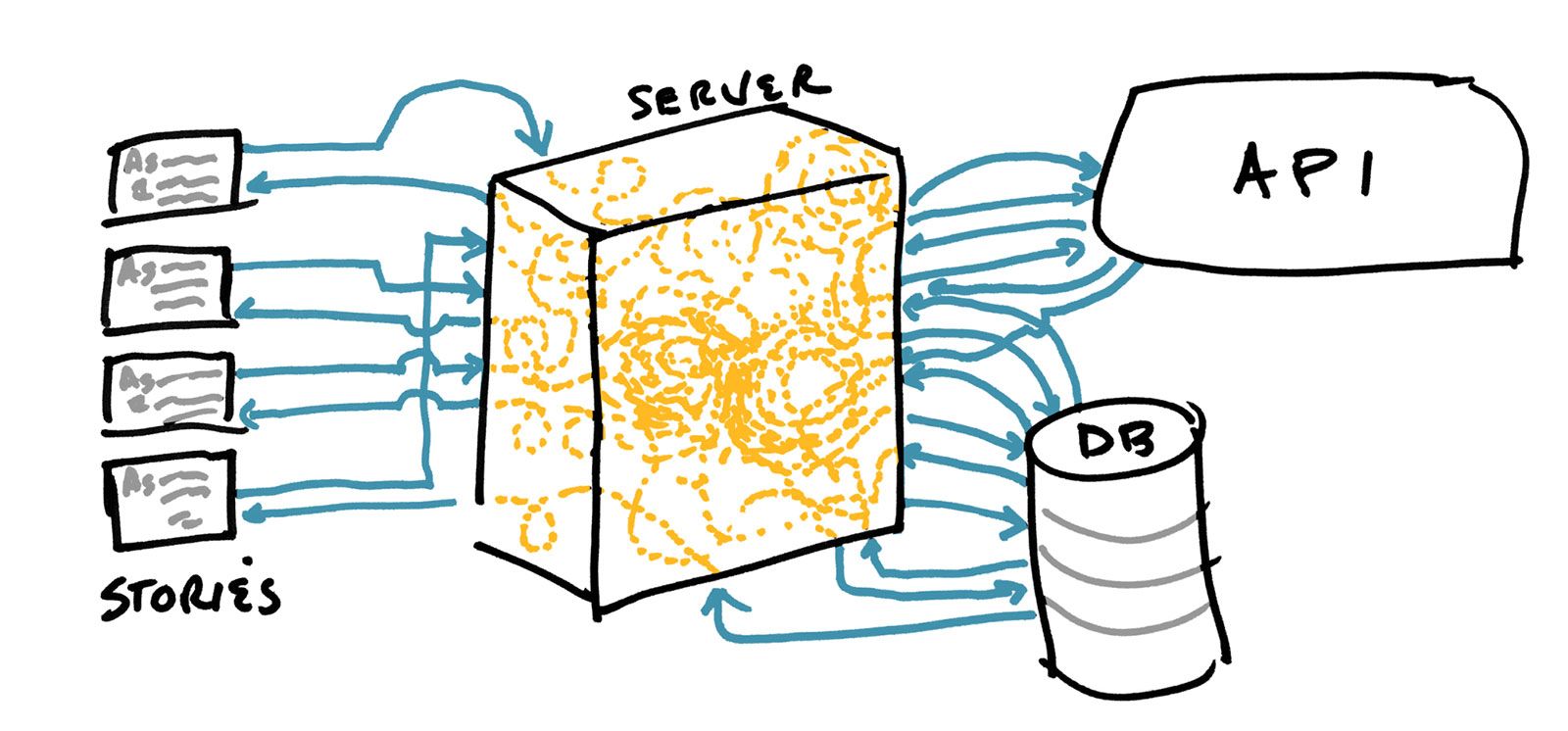

*Without good software design techniques, your code can become a mess as you fulfill more user stories.*

*Without good software design techniques, your code can become a mess as you fulfill more user stories.*

Without a guiding architectural map, how does a team keep the code clean and useful?

This is where the second notion of “design” guides a project: software design.

You can think of software design as a discipline of keeping code small, modular, and decoupled. Instead of a 20 line function, the engineer breaks up functionality into six smaller methods that each play a little part. Instead of every object knowing about every other object in the application, objects are handed the things they need to accomplish their tasks.

If we think about these modules as bricks, then their independence and flexibility makes it easy to construct almost anything: a retaining wall, a house, a palace. Smaller modules aggregate into bigger modules. Groups of modules can become a service. User stories about security and performance can build out all the shapes and lines in an architectural diagram.

Focusing on software design turns the process of getting to architecture on its head. Instead of drilling down from an architectural map into services and code, we promote and organize code into an architecture. There are two huge wins to this approach:

- The abstractions were grown from the code and product itself and are a better fit than ones imposed from on high.

- The modules of code are decoupled and can be rearranged when needs change.

How to make great software designs

Seemingly since the dawn of programming, engineers have been concerned with making code more modular and flexible. In that time, we have developed great guiding principles.

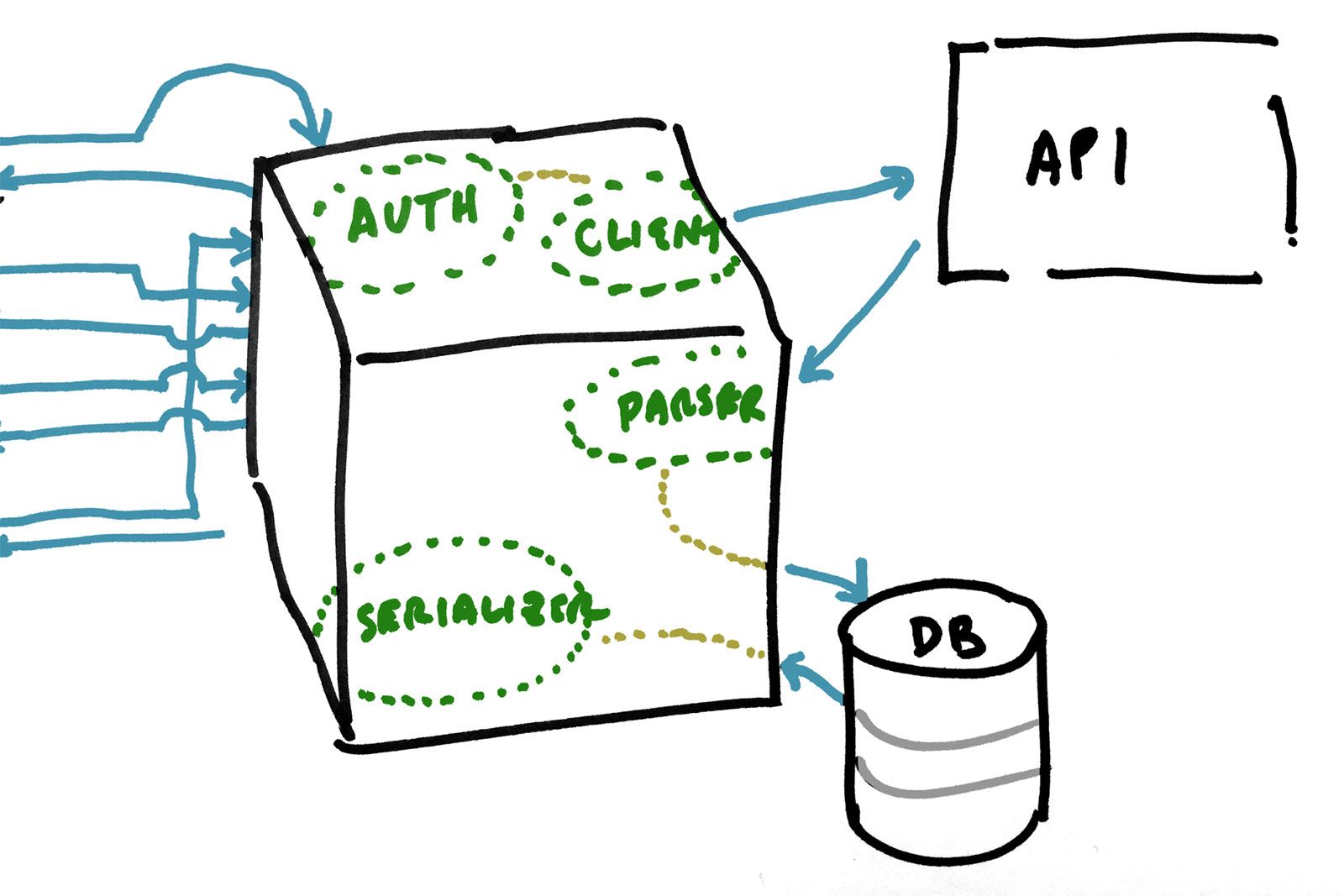

*Using refactoring to impose design on the chaos that happens with continual development.*

*Using refactoring to impose design on the chaos that happens with continual development.*

SOLID

SOLID is an acronym where each letter stands for a particular object-oriented design principle. Despite its object focus, SOLID has proven itself useful across programming paradigms. Many have argued that SOLID can be boiled down to its first principle: single responsibility. This principle states that every module should have just one purpose.

To make this distinction more concrete, imagine an application being created by an agency. The agency is connecting to data being created by a non-governmental organization. This external organization has created a great API that makes it easy for the agency’s engineers to get the data they need. During the course of developing many user stories, the engineering team realizes they have consumed data from that service in three, slightly different ways.

They apply the single responsibility principle to make the design better. They look at the three places that they’re connecting with the API and see two patterns:

- An authorization process has to be part of each request to the API.

- The data coming back is parsed in very similar ways once received.

The agency engineers create an API client object that handles the authorization. Then they create a parser that takes apart the data consistently.

Wrapping up this logic in one place means that they’re inoculated from massive changes, when they happen. When the non-governmental organization decides to radically change the way they’re sending out data, it changes in one place instead of three. When the agency connects to their API in a number of other ways, and then the API changes their authentication flow, that too changes in just one place.

The other SOLID principles, which I leave to your personal research, are also concerned with reducing the cost of change by making code smaller and simpler.

Optimize for change, but don't optimize in advance

"The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry." — Robert Burns

Often when building software, we engineers are building something simple and imagine that it will surely need more features soon. Being prudent, we often choose to build those features now. Sometimes it’s a security feature; sometimes performance; sometimes a more polished graphical design.

As good as these intentions always are, the additions make the code complicated and hard to work with. They lead to an increase in defects and reduced velocity. These defects often decrease performance and security, in direct opposition to their goals.

While it’s true that change is inevitable, optimizing for change dictates that we keep things clean, simple, and decoupled.

When the desire to add optimizations arise the product team needs to be an informed partner. They should make priority decisions and separate concerns into new user stories.

Commit to refactoring

The right abstractions for a growing, breathing software project cannot be guessed correctly in advance. Trying to make that guess is the “optimizing in advance” that we advise against. Instead, wait for patterns to emerge and then refactor.

Martin Fowler introduced a helpful guide called the rule of three. Duplicate code should be tolerated twice, but when a third instance is needed, it’s time to refactor out an abstraction to remove that duplication. This idiom may seem to stand at odds with the single responsibility principle, but good design requires the right abstractions, not just adherence to principles. It’s often impossible to understand the real duplication when presented with only two examples. Some teams I’ve worked with have required four examples to build the right abstraction.

Software teams need to recognize that continual improvement leads to much higher velocity in the short- and long-term. While changing to a practice of continually refactoring initially impacts velocity, once it’s part of the practice, everything works faster and better.

There is still a place for architectural planning

User stories and good software design practices will grow architecture organically.

There are a few decisions that still require us to think about architecture first. Languages and frameworks have an impact on team culture and the ability of the team to recruit top talent. Choose languages and frameworks that are modern, open source, and well-supported. Database technologies can be abstracted with adapter layers, but it’s still important to carefully consider your needs and the implications of your choices.

Breaking software into individual services allows multiple teams to work on the same system at once. This optimization into services should follow the successful implementation of many user stories that follow user personas from end to end. This will make sure the system works as a whole.

Focusing on design over architecture is a paradigm shift that forces teams to think about the problem from the outside in. The win in this approach is that there is no last minute integration step when a team hopes that all the parts work together. Choosing design over architecture wins by reducing project risk.