In the last post, we talked about the potential consequences of having a lot of technical debt. Now, we’ll give you concrete steps to identify and then manage that technical debt so it doesn’t get out of hand.

To manage it effectively, you need to:

- Identify what debt you have

- Make it visible for decision-making purposes

- Decide what to do about it (for example, pay it off, live with it)

- Implement changes to reduce or eliminate the effects of it

Identifying technical debt

It’s easy to tell how much financial debt you’re in by looking at your various account statements (mortgage, credit cards, etc.). Technical debt, on the other hand, isn’t so obvious, which can make identifying it a challenge. Thankfully, there are a number of indicators (or warnings to look into something more deeply) that can help you and your developers recognize it.

-

Slowing rate of velocity. Velocity is a measurement for how much work a development team can complete during a particular interval (for example, two weeks). Assuming all other things are equal (for example, team composition hasn’t changed), if velocity starts to slow down over the course of several iterations, it maybe a sign that too much technical debt has piled up and is now impairing development productivity.

-

Stressful releases. If the development team is under extreme stress at the end of a release cycle, technical debt may be the underlying cause. You’ll know something isn’t quite right with the codebase if the release process requires the development team to go into “crunch mode” to fix unforeseen problems such as broken integration builds and software crashes.

-

Aging libraries. If your software uses libraries for which new versions exist, that represents technical debt. When those libraries are a “major version” behind (e.g., EJB 2 vs. EJB 3, Devise 1 vs. Devise 3), or worse, and are no longer being maintained, then your project is deep in technical debt.

-

Defects. Defects, or bugs, can tell you a lot about the state of your product’s quality. High-functioning agile teams fix bugs as they’re found and don’t let them accumulate. For example, if the number of open defects or escaped defects is trending up over time, that’s a strong indicator of technical debt.

-

Low automated test code coverage. Code coverage tools can automatically tell you how much of your software’s code is covered by a set of automated test cases, which are written using testing frameworks such as JUnit (for Java) and RSpec (for Ruby). Developers often look at what percentage of the code is covered by unit tests to gauge its quality heuristically, at least in terms of maintainability. There’s debate among the development community as to the meaningfulness of a target metric for unit test code coverage, but they generally seem to agree that coverage of more than 90 percent is a good sign, and anything below that is potential cause for concern. For example, coverage of less than 75 percent may indicate a serious problem.

-

Other software quality measurements. In addition to code coverage, there are a number of other useful software quality metrics that can be automatically measured using tools such as SonarQube. For example, coding standards violations, cyclic dependencies, cyclomatic complexity, and duplicated code. For each of these example metrics, the lower the measured value, the better the quality.

-

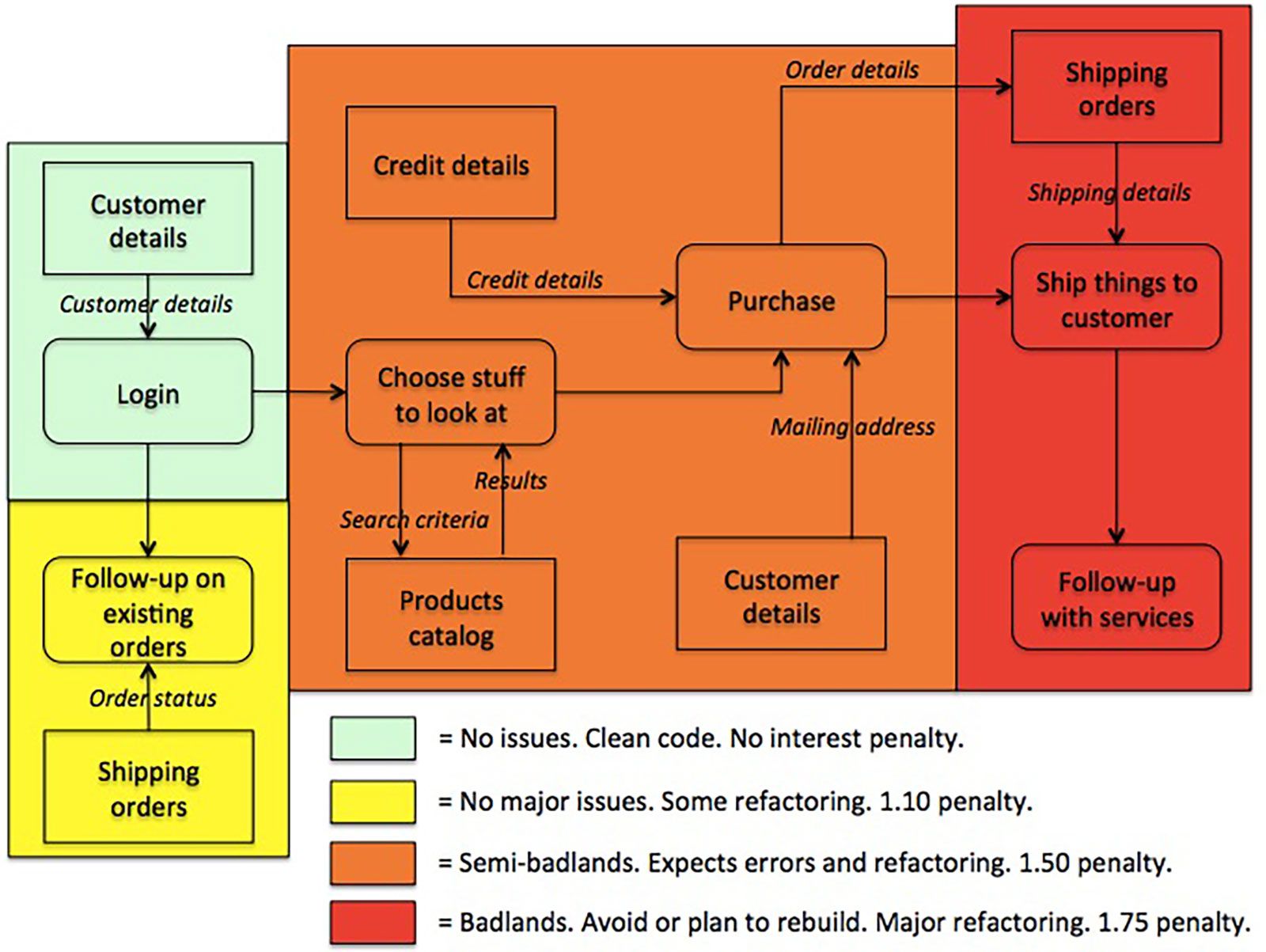

Heat map. A heat map is a great tool to understand where your technical debt lives. To create a heat map, ask the development team to model the components of the software, and shade or color each one to represent the relative complexity of adding new features or making changes to that section of the system. In other words, where to expect smooth sailing or rough waters. Things such as spaghetti code, lack of automated test code coverage, etc. might be why some areas on the map are more challenging than others. See below for an example of a heat map.

-

General code smells. Code smells indicate a potential weakness in the design of the software. They aren’t usually bugs, which prevent the software from functioning properly, but rather are “certain structures in the code that indicate violation of fundamental design principles and negatively impact design quality” (Wikipedia). Examples include duplicated code, long methods, and classes with too many instance variables. Such design weaknesses could be slowing down development or increasing the risk of bugs or failures in the future. Encourage your developers to be on the lookout for code smells, and when they “smell” something, have them check it out to determine whether there’s really a problem.

Making technical debt visible

After you’ve identified where the technical debt lives within your codebase, the next step is to make it visible to the entire team, including management, for decision-making purposes. The challenge here is to provide sufficient information about what work needs to be done, as well as associated costs, benefits, and risks, so that the team can make smart tradeoff decisions between fixing technical debt or building new features. Non-technical stakeholders tend to favor the latter, which can quickly lead to an out-of-control system. Here are three approaches to help overcome this bias.

The first approach is to factor technical debt into the cost of development, which yields a greater understanding of the value of paying it back or not paying it back. You can do this using our friend, the heat map, like the one shown below.

*Source: [Modified from a post by James

King](http://kingsinsight.com/2010/07/31/estimating-the-impact-of-technical-debt-on-stories-heat-maps/)*

*Source: [Modified from a post by James

King](http://kingsinsight.com/2010/07/31/estimating-the-impact-of-technical-debt-on-stories-heat-maps/)*

As you can see, each software component is colored to indicate the relative complexity in working with that section of the code. There’s also a numeric factor associated with each color. This represents the additional effort, or interest penalty, that a developer should factor in when estimating a task. For example, a change to a red-colored component originally estimated at four hours should be revised to seven hours (four hours multiplied by a factor of 1.75), or three hours worth of extra effort. This is an excellent way to shed light on what the interest penalties of carrying too much technical debt are.

The second approach is to maintain a technical backlog that defines technical work packages. Each package should convey the following pieces of information:

-

A brief description of the work that needs to be done (for example, restructure the authentication code within the User class by moving it into its own Authentication class)

-

An estimate of how long it will take to fix the debt (for example, three hours, two story points)

-

An estimate of the amount of debt that is inherent in the code, which doesn’t need to be precise and can therefore be expressed using an ordinal scale (for example, “low,” “medium,” or “high”)

-

An estimate of the probability that the section of code will be read or changed in the future, which again can be expressed using an ordinal scale

The third approach is to monetize technical debt using tools such as SonarQube. These tools calculate the cost to fix the technical debt accumulated in a product. For example, they might report $2 million of accrued debt in an application with 500 thousand lines of code, which would require spending $4 per line of code to pay back the debt. Not only can these tools report technical debt at a macro level, but also at a micro level. For example, detection of a specific block of duplicated code and the associated cost to fix it.

Regardless of which approach you use to make technical debt visible to decision makers, expressing the cost of it in quantitative terms (for example, dollars, labor hours, or story points) allows you to establish credit limits on how much debt the product can accrue. For example, when the technical debt reaches a certain level (for example 25 cents per line of code), all new functionality is put on hold until the debt is reduced to acceptable levels. This forces the product team to invest in controlling debt before things get out of hand.

Deciding what to do about technical debt

After you've made your technical debt visible for all to see, the next step is to decide what to do about it. Frank Buschmann describes three debt payment strategies:

-

Debt repayment. Refactor or replace the code, framework, or platform that is considered technical debt and is giving you a headache. (For those unfamiliar with the technical jargon, refactoring is the process of improving or simplifying code without changing the functionality.)

-

Debt conversion. Replace the current solution with a “good, but not perfect” alternative. The new solution has a lower interest rate. This might be a good option if a perfect solution is exceedingly expensive to build.

-

Just pay the interest. Live with the code. This might be a good option if: (a) refactoring is more expensive than working with the not-quite-right code; (b) the code is rarely, or never, read or changed; (c) the code doesn’t implement important requirements and therefore doesn’t need an elegant solution; or (d) if the system has reached its end-of-life or will be redeveloped.

As a general principle when deciding which payment strategy to use, you want to make sure that the important parts of your code are as clean as (economically) possible.

Resolving technical debt

After deciding upon the payment strategy, the next step is to implement the fixes to your product. This requires fitting the work into your development cycles:

-

Refactor with every feature or fix. Every time there is a new feature that depends on code that is fragile or bug-ridden, include extra time to create a sound foundation for the new improvements.

-

Quality improvement every iteration or release. The product development team sets aside a dedicated percentage of time (for example, 10 percent) every iteration or release to pay down technical debt. If for any reason there aren’t any priority bug fixes, the team can work on improving test coverage and refactoring areas of the codebase that will likely be needed for upcoming sprints.

-

Quality-focused release. The team budgets time for a release dedicated solely to fixing a big batch of bugs, cleaning the codebase, and reworking the architecture. This is great for when extensive changes are required.

-

Managing the product backlog. If you’re using an agile methodology such as Scrum, you can capture technical work packages (described above) as user stories and include them in the product backlog. You can then prioritize these user stories for implementation during an upcoming iteration cycle.

In our next post, we’ll go over ways to can prevent your next project from accruing technical debt in the first place.