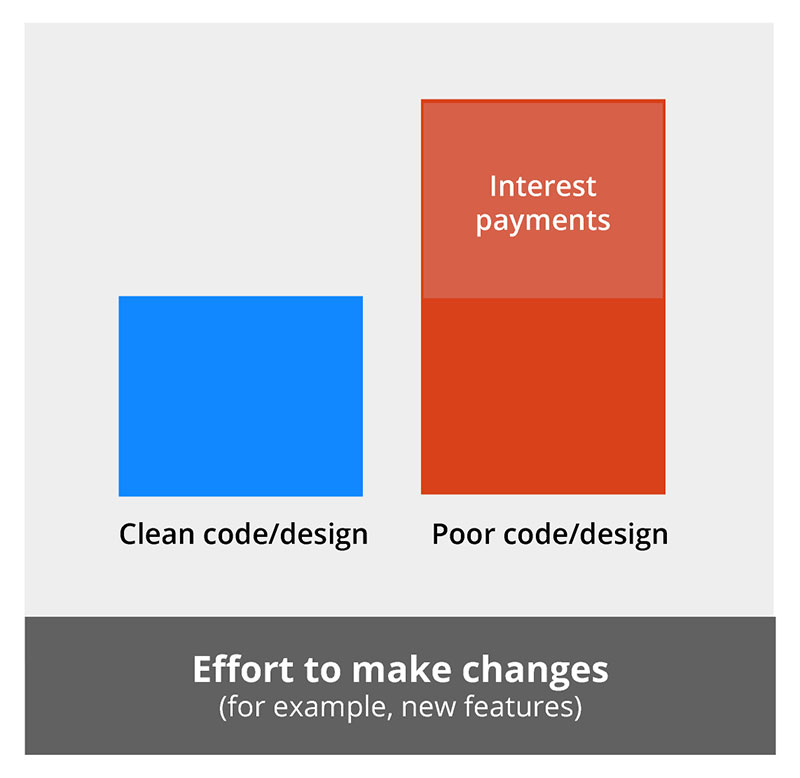

Let’s assume we’re developing a software product. When we make short-term compromises to its code or design quality, we’re making the product more difficult for someone else to continue to develop, test, and maintain in the future. This is the concept of technical debt (explained more in the first part of this series), which is similar to financial debt. For example, the extra effort required to finish our incomplete work represents the principal portion of the debt. And the extra time it takes to work with our unwieldy code or design, until it’s fixed, represents the interest portion.

Like financial debt, not all technical debt is bad debt. For example, taking out a mortgage on a home that you pay back within 15 years and sell for a 175 percent return is good debt. Conversely, racking up a huge credit card balance on a luxury yacht with no means to pay it back is reckless.

With software, it’s perfectly reasonable to release early with known limitations in order to capture a time-bound market opportunity or meet a compliance deadline, as long as there’s staff in place to address those limitations after the launch. Another great way to leverage technical debt is to quickly run a market experiment (a la lean startup). If the experiment doesn’t yield the desired results, you can remove the feature, and not even bother repaying the debt. That would be a waste. Of course, if you keep the feature, then it must be finished, and you can do that with the benefit of what you learned from the experiment. So the aim shouldn’t be to achieve a completely debt-free product. Instead, you want a product with whatever level of quality is necessary to give the development team enough stamina to go faster for longer.

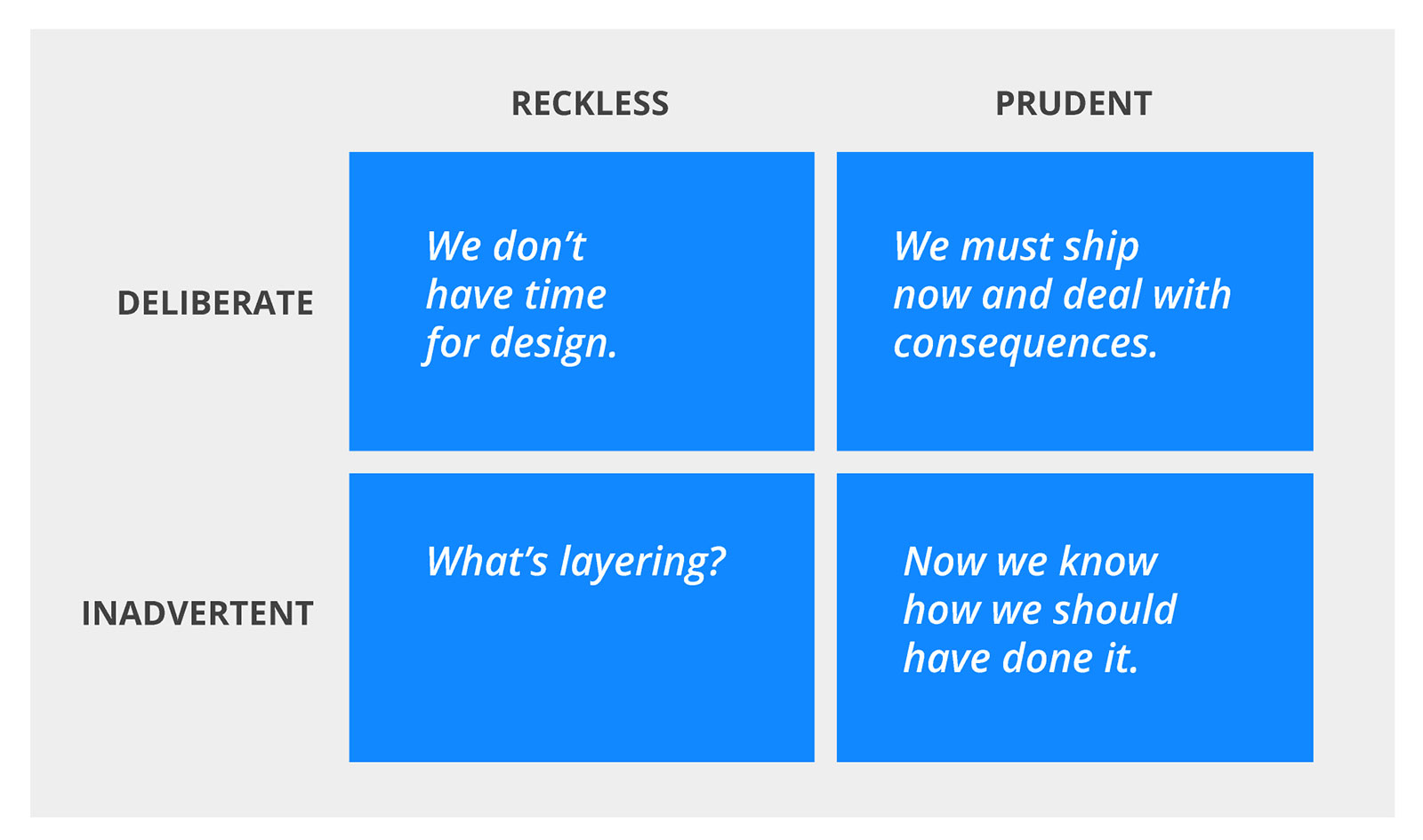

Just as you’ll find in the financial world, there are different kinds of technical debt. Martin Fowler, a leading software expert, classifies technical debt into four types, as shown in the quadrant below.

Here’s how each type may occur:

-

Reckless/Deliberate Debt — The team feels time pressured, and knowingly violates best practices without any forethought into how to address the consequences. Another scenario: management lacks sufficient funding to hire enough senior experts to direct and review the work of junior programmers, but decides to take the risk anyway.

-

Prudent/Deliberate Debt — The team decides that the value of shipping a “quick and dirty solution” now is worth the cost of incurring debt. They’re fully aware of the consequences, however, and have a plan in place to address them.

-

Reckless/Inadvertent — The team is ignorant of best practices, and makes a big mess of the codebase.

-

Prudent/Inadvertent — Even with great programmers, the team delivers an extrinsically valuable solution, only to realize how they should have (intrinsically) designed it. (Often the process of software development is as much learning as it is coding.)

What are the consequences of technical debt?

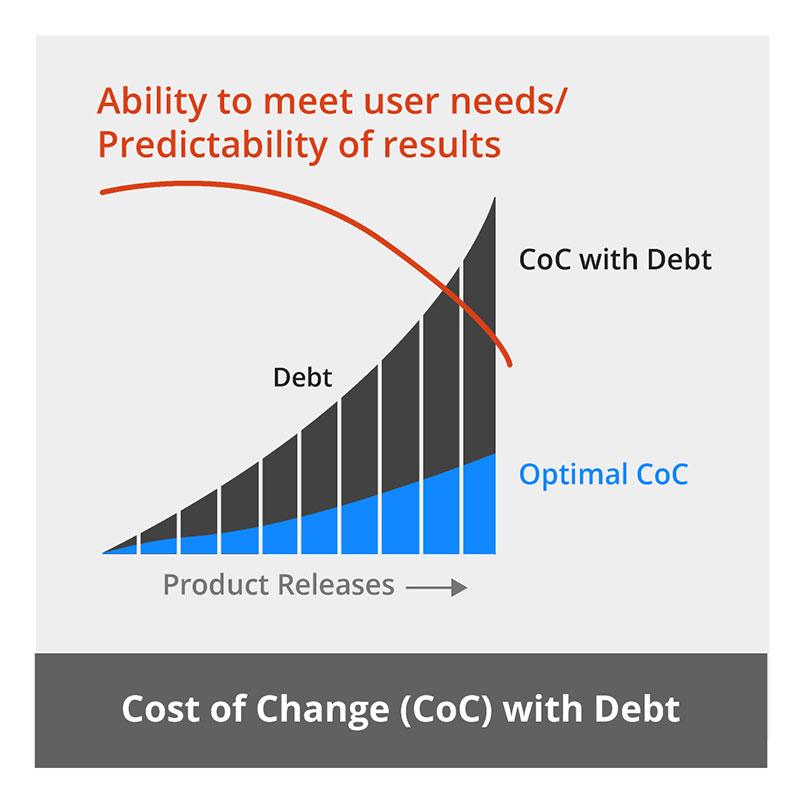

From annoying bugs to crippled projects, the effects of technical debt manifest in a variety of pernicious ways. Jim Highsmith’s technical debt curve, modified below, illustrates what happens as technical debt grows within a software product over time:

-

The cost (or difficulty) of change increases, eventually to the point of unmaintainability

-

The ability to respond to the needs of customers decreases, making them extremely unhappy

-

The predictability of results decreases, making management highly distrustful. (Producing accurate estimates for software with a high amount of debt is nearly impossible.)

Source: Jim Highsmith

How do projects end up on the far right of the curve? And why is that a bad place to be? As Highsmith explains:

One problem with technical debt is that the impact can be slow growing and somewhat hidden. To the question ‘Fix the technical debt, or build new features’ we know how it is usually answered. As it gets worse customers complain about slow delivery, increasing the pressure to take more short cuts, which increases the technical debt, which slows the delivery process, which increases customer dissatisfaction, in a rapidly spiraling vicious cycle. Unfortunately, by the time many organizations are paying attention, all the solutions are bad ones: 1) do nothing and it gets worse, 2) re-place/re-write the software (expensive, high risk, doesn’t address the root cause problem), or 3) systematically invest in incremental improvement.”

Customers aren’t the only ones who suffer the consequences (annoying bugs, missing features, etc.) of technical debt:

-

Friendly help desk staff will field more support calls

-

Software operations team loses sleep patching the system all hours of the day

-

Management gets bad publicity due to bugs, delays, security issues, or outages

-

Developers have to deal with the bad work of other developers, which may cause turnover

Now that you understand what technical debt is, we’ll discuss how to manage it in our next post.