Security compliance is a major factor in launching a software system in the federal government, in terms of technology choices, and even more importantly, time and effort. The Authority To Operate compliance process for systems within our division of the General Services Administration (GSA) was taking more than six months for every system, with a long and growing backlog. With the new process, we have cleared the backlog and reduced the turnaround time to under a month. We think that deserves a celebration and makes for a good opportunity to share the lessons we’ve learned.

If you’re reading this and thinking “My work has nothing to do with ATOs,” don’t despair! Even outside of security compliance, the Sprinting Team model can work well when you have a handful of disparate people who are otherwise asynchronously involved in a time-intensive, complex process with a clear target. For example: a long list of job applicants to review, procurements to complete, etc.

Background

Every federal information system must go through the Risk Management Framework created by the National Institute of Standards and Technology before it can be used to process federal information. This process culminates in an agency issuing a signed Authority to Operate (ATO) for that system. Basically, that ATO certifies that an authorized person has said “yes, I trust that this system and team are doing their due diligence security-wise, and I am ok with the inherent risk of launching it.” Getting there is colloquially known as “the ATO process”.

One year ago, the Technology Transformation Services (TTS) had 25-30 systems (of varying sizes) that needed new ATOs: some were expired or expiring, some had only completed part of the process, some hadn’t been considered part of our system inventory, etc. ATOs across government have traditionally taken 6-18 months, with a lot of slow back-and-forth between system owners and the assessors. The ATO Sprinting Team brought the assessors and the project teams “into a [virtual] room” for focused sprints to get through one ATO at a time, with near-full-time focus.

Under the ATO Sprinting Team, our ATOs have gone down from more than six months to under a month.

How did we get there?

18F launches new software all the time, and since ATOs are such a big part of doing so, we’ve identified a number of ways to make ATOs faster:

- Reduce the complexity of the system. The larger the system, the larger and more complex the ATO “packages” (documentation) will be. This makes them harder to create and harder for assessors to evaluate. The smaller the systems, timeframes, and packages, the easier for everyone.

- More focused process. There is a switching cost when people try to multitask; this applies to our project teams trying to do their ATO while doing feature development and assessors reviewing multiple systems at once. The more focused everyone involved is on the ATO, the fewer the human-hours to complete it.

-

Use consistent tooling and processes. Assessors are there to ensure the system meets the compliance requirements, and to do so, they need to understand what’s going on in the system. If every system they look at is using an entirely different framework, infrastructure, or monitoring, it’s harder for them to assess. By documenting our standard security practices and ensuring teams follow them before they enter assessment, we:

- Avoid reinventing the wheel for every system

- Reduce the learning curve to understand each system for assessors

- More inheritance. As noted in the “smaller” and “more consistent” bullets above, the more custom parts of the system, the more complex the ATO process. The more we reuse a proven technology stack the fewer security requirements need to be addressed by the system under evaluation.

- By standardizing a few ways to do user authentication, each system doesn’t have to assess a new technology for the same functionality.

- By leveraging cloud.gov for (nearly) all of our backend code and databases, we cut out a huge amount of operational and compliance burden.

- Sites deployed on Federalist can be folded in to the Federalist ATO. Sites on Federalist can be assessed and authorized in a matter of days.

- More integration between security and project teams. Similar to “more focused” above, having all ATO process interactions happen asynchronously over email means that open questions and blockers can’t be resolved right away, and details can be lost. Having the security team / assessors working alongside the project team in real time means that these issues can get resolved quickly, and the entire process is more collaborative.

To implement these, we needed a well-functioning team. Here’s how it was structured:

Roles

The Sprinting Team consisted of:

- Security. This usually consisted of someone who focused on the documentation and assessment of the overall system, as well as a penetration tester.

-

The System Owner. This was generally a TTS developer on the project team who had a good understanding of the system going through the process, who can:

- Answer questions about the system

- Fix things as they come up, or at least take those issues to the appropriate person

- An Infrastructure Lead. A TTS team member with ATO experience who can help with preparation for the assessment, and translate between Security and the System Owner.

We were able to get Security members involved across multiple sprints, so they would learn with us, participate in retros, and be able to act on those outcomes.

Tracking

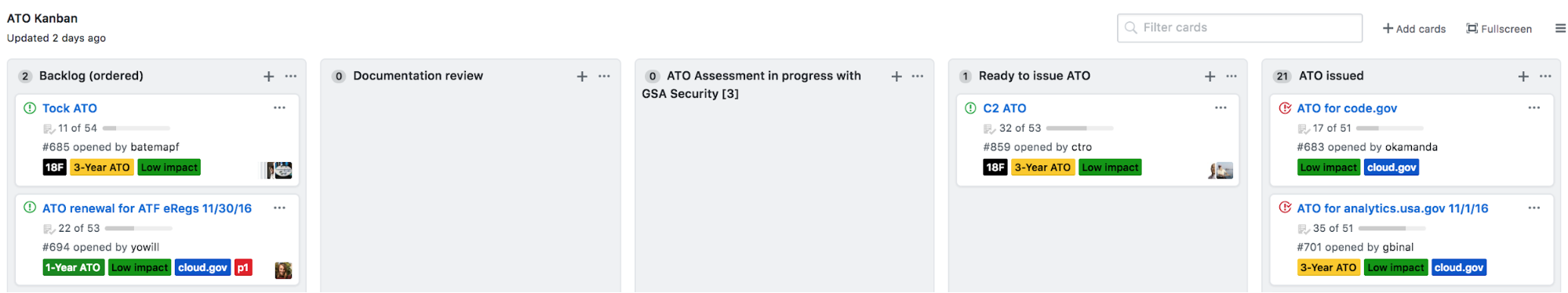

The Infrastructure Leads keep a kanban board to track the status of ATOs:

Systems are prioritized based on their launch deadlines, whether they have an existing ATO that’s expiring, and preparedness of the project team. We limit ourselves to at most one ATO in active assessment at any given time.

We also keep track of system launch dates, to make sure we’re getting ahead on ATOs before it’s a time crunch. The ATO Sprinting Team model was focused as much on reducing the passive time an ATO wasn’t getting done as the active time working on it.

Artifacts

As systems move through the ATO process, we learn more and more about what works well for systems compliance-wise.

Almost all of the systems run on top of cloud.gov, a Platform-as-a-Service with a FedRAMP authorization, which handles a lot of the compliance at the platform level. For the parts that are the responsibility of the customer system, we worked with GSA Security to develop a System Security Plan (SSP) template for systems running on cloud.gov, which cut out the security controls handled by the platform.

Working in the constraints of what Software-as-a-Service was approved or could be approved for use at GSA, we also standardized tools, procedures, and control language around:

We have the advantage of building and launching systems constantly, so we have lots of opportunity to learn and iterate on the ATO process.

Challenges

There were a handful of issues we ran into:

- Experience. Every System Owner going through our ATO process was doing so for the first time. This meant that they don’t know how to fill out System Security Plans, what a security control is, what happens during a penetration test, etc. On top of that, security compliance can be frustrating because of its complex requirements and jargon. This meant the Infrastructure Leads had to not only be knowledgeable about security compliance, but also be patient coaches.

- Measurement. ATO processes are largely human, so gathering data about the start and stop of each stage for every system to date took hours of combing through dialogue in our chat and email conversations, kanban board, and PDFs of signed ATOs.

- Communication. The ATO Sprinting Team would constantly improve the process and guidance as we went, but System Owners weren’t always aware of the changes, and would sometimes get frustrated at moving targets.

Things to watch out for

If you are at another agency and are interested in applying the principles of an ATO Sprinting Team, make sure to:

- Get buy-in from the Security team. We were lucky to have willing and capable partners in GSA Security. A Sprinting Team only works if all the stakeholders are willing participants.

- Get people dedicated to working on this. Our Infrastructure Leads have to understand the process, make judgement calls, and shepherd project teams through. You need people able and willing to commit the time.

- Think of ways to measure. As mentioned earlier, we didn’t think about metrics early enough, so determining our success quantitatively was a backwards-looking, manual process. Determine your success metrics early, implement the collection early, establish a baseline, and review them regularly.

The results

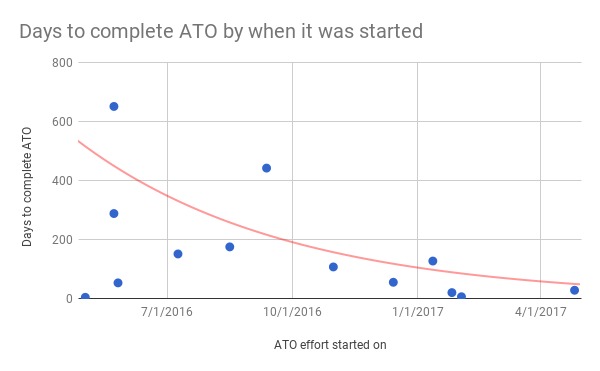

As mentioned above, we have been dramatically improving the time to ATO:

“ATO effort started on” is measured from when we acknowledged “this system needs an ATO” and created a card in our Backlog. “Days to complete ATO” is measured from the card creation time to when the ATO letter is signed.

Congrats to the Sprinting Team for clearing the backlog, our GSA Security counterparts for being so great to work with, and all the systems that went through for achieving compliance!

See also

- Before You Ship - 18F’s guide to ATOs and Infrastructure

- “To get things done, you need great, secure tools” blog post

- FedRAMP Accelerated

- Project Boise - discovery on compliance processes across government

- How cloud.gov helps teams comply with requirements