Well, we sure didn’t expect this. But the winning bid for the first iteration of the 18F micro-purchase experiment was $1. And, on Wednesday, the winner delivered a solution that passed our acceptance criteria.

We conceived of this experiment with a couple goals in mind: to explore a new method of software contracting, to attract new companies to work with the government, and to help advocate for the value of open source code in the federal government. After this first iteration, we feel that micro-purchasing has the potential to achieve those goals.

The experimental nature of this project was important. We designed it to have minimal financial risk, while providing us with plenty of learning opportunities. Based on the first iteration, we’ve already learned a lot about the market for open source micro-purchases, the design of this experiment, and how we can best administer future bidding processes.

As a quick recap, our first iteration of the experiment was to use a “reverse auction” for a discrete requirement for the CALC product. In the reverse auction, vendors could bid down the price and the vendor with the lowest price would win the opportunity to produce a working solution in 10 days. After a few days of bidding, the winning bid came from Brendan Sudol. In less than a week, the requirements were met.

We asked for labor category data from the Schedule 70 to be loaded into CALC. Not only did Brendan Sudol meet the requirements of loading the data, the new code had 100 percent test coverage, an A grade from Code Climate, and included some new functionality to boot.

But beyond the fact that we got working software in a little less than a week after the bids closed, the experiment revealed some fascinating data points, including the following:

- We had 16 unique bidders with validated SAM.gov registrations.

- Of those bidders, half of the bidders registered for SAM after our blog post announcing the experiment.

- At least eight of the bidders were small businesses, including woman-owned small businesses, minority-owned small businesses, and service disabled veteran-owned small businesses.

- The largest bid increment was $740, the smallest bid increment was $1, and the most common bid increment was $50.

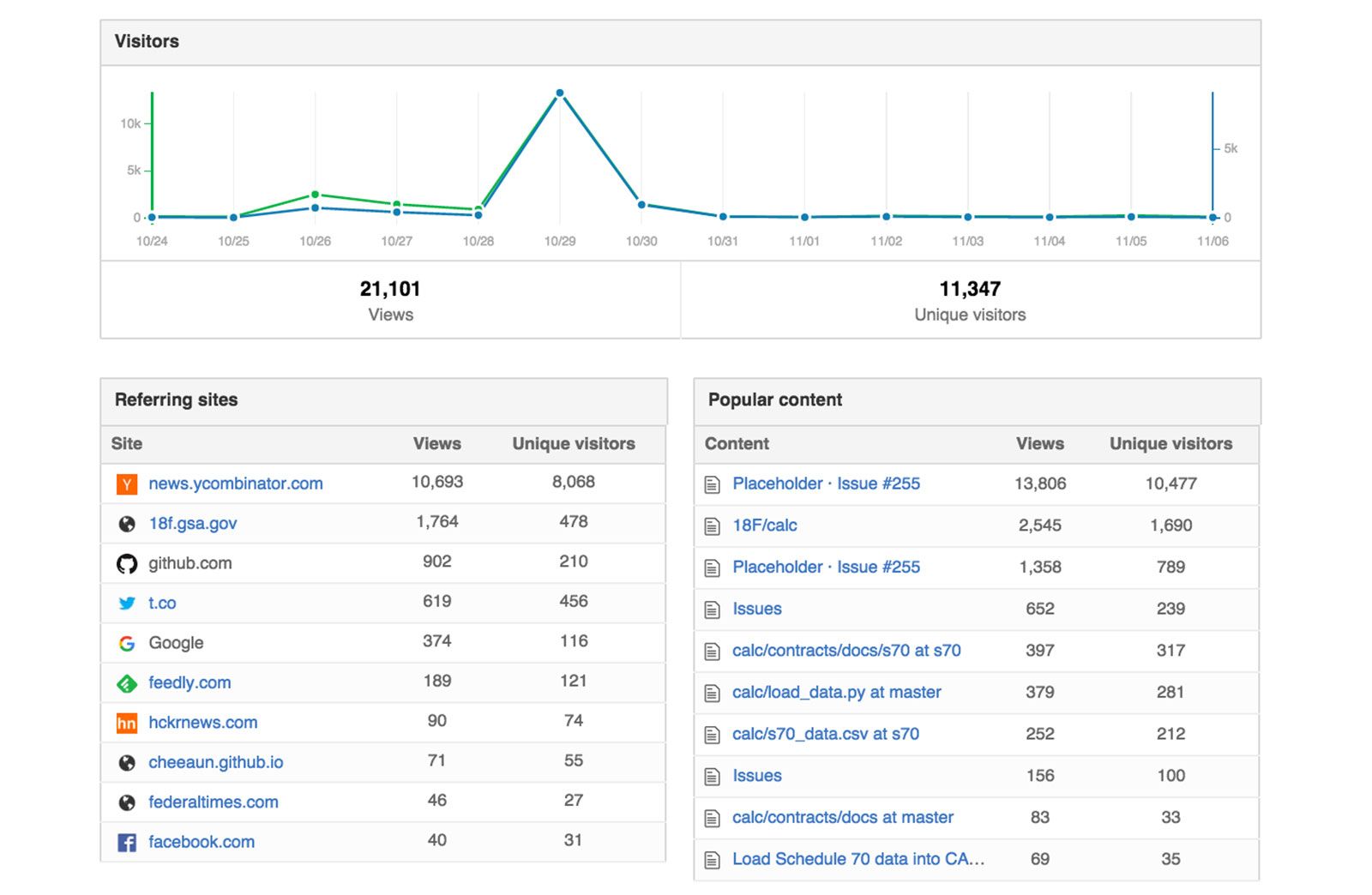

- As of the afternoon of November 6, 2015, there were more than 10,000 unique visitors to the GitHub issue (though much of it was driven by being on the front page of Hacker News), and more than 300 unique visitors to the underlying data that is the subject of the micro-purchase experiment.

*A snapshot of the analytics for the CALC repository on GitHub.*

*A snapshot of the analytics for the CALC repository on GitHub.*

Given these statistics, we think it’s fair to say that there is a market for open-source micro-purchasing, though we obviously will need to spend some time and effort refining our methods.

There were also process and technical hiccups. When we initially announced the experiment, we were working on a lightweight platform to facilitate bids. We announced that the experiment would go live on October 26, 2015, expecting that we would have the platform ready to go. It wasn’t. We overestimated our internal velocity, and we felt that it was not sufficiently tested to go live. So we pivoted and used a Google Form. This is the reverse of how it should have been: we should have started with the Google Form and then worked on the platform. We optimized too early. But we’re acknowledging it here, and we’ll learn from it on the next iteration.

The Google Form itself had some weird quirks. The Google Apps Script we used, though tested, had some unexpected behavior in production related to the Form Submit trigger. As a result, it was possible for people not to know whether they were the leading bid.

Then, there was the $1 bid.

When we received the $1 bid, we immediately tried to figure out whether it was intentional, whether it was from a properly registered company, and whether we could award $1. We contacted the bidder and we confirmed that the bid was valid, that the registration on SAM.gov was current, and that the bid would be the winning bid. It was a plot twist that no one here at 18F expected. This unexpected development will no doubt force us to rethink some of our assumptions about the reverse-auction model.

In some respects, this result was the best possible outcome for the experiment. It proved that some of our core assumptions about how it would work were wrong. But the experiment also validated the core concept that open-source micro-purchasing can work, and it’s a thing we should try to do again. A few weeks ago, micro-purchasing for code was just an idea, but now that we’ve done our first experiment, the data demonstrate that the idea has potential and can be improved upon.

If you’d like more information on future micro-purchases, you can sign up for email updates here.