If you have ever led or managed a web project, you know that coordinating a team of software engineers is hard work! When your software team presents you with options, it’s not always easy to know what to choose and why to choose it.

We’re four software engineers with Technology Transformation Services who can advise product owners in government about one of the first choices any new web application will face: choosing a web application architecture.

We’ve seen software engineering teams use newer and more complex technologies, when a simpler option could better serve the project and the public. Our Engineering Practices Guild met to discuss this topic in November 2020, and wrote up the results of our discussion in the TTS Engineering Practices Guide.

We hope this blog post can help you understand the concepts behind this decision-making so that you can steer your software towards simplicity — even if you don’t have direct software engineering experience.

Why choose the simpler option?

Let’s start with the “why.” Government software projects often face tight budgets, are used long-term, and have a broad user base with diverse needs — all of which push us to think that simpler is better.

- Cost-effectiveness: Software costs money to build, improve, and maintain. Software decisions have budget impact over the long term. The more complexity in your web architecture, the more you will need to spend in the long run — on activities like running your product, keeping it secure, and improving it over time based on user feedback.

- Maintainability: People who take on product owner roles in government often wear multiple hats and are juggling multiple roles. The same goes for technical staff in government. They are often overstretched! Because time and attention are valuable, push for software that is less complex — it will be easier to maintain in the future.

- Accessibility: As government employees, we serve the public, so the websites we build must be highly accessible to the public. When choosing a web app architecture, ask your software team members about the accessibility impact of their proposed choices. More complex architectures, like Single Page Apps, can be less accessible by default and require more work to build in an accessible way.

- Performance: We’ve seen applications that use complicated web architectures in government that take a long time to load, even when loading relatively simple data. Another reason to choose the simpler option when possible!

What’s simpler in technology?

In order to best evaluate what’s simple, it’s important to think about the main problem you are trying to solve. What’s the simplest way to solve the problem? Simpler approaches involve:

- Fewer layers of technology

- Using stable technology over cutting-edge

- Less complexity when possible

Below is our outline of different web application architectures that you might choose from when launching a new website or web app. We aimed to put these in order of simplicity, starting with the choices that are easiest to build and maintain over time.

If you can make it a static site, you should.

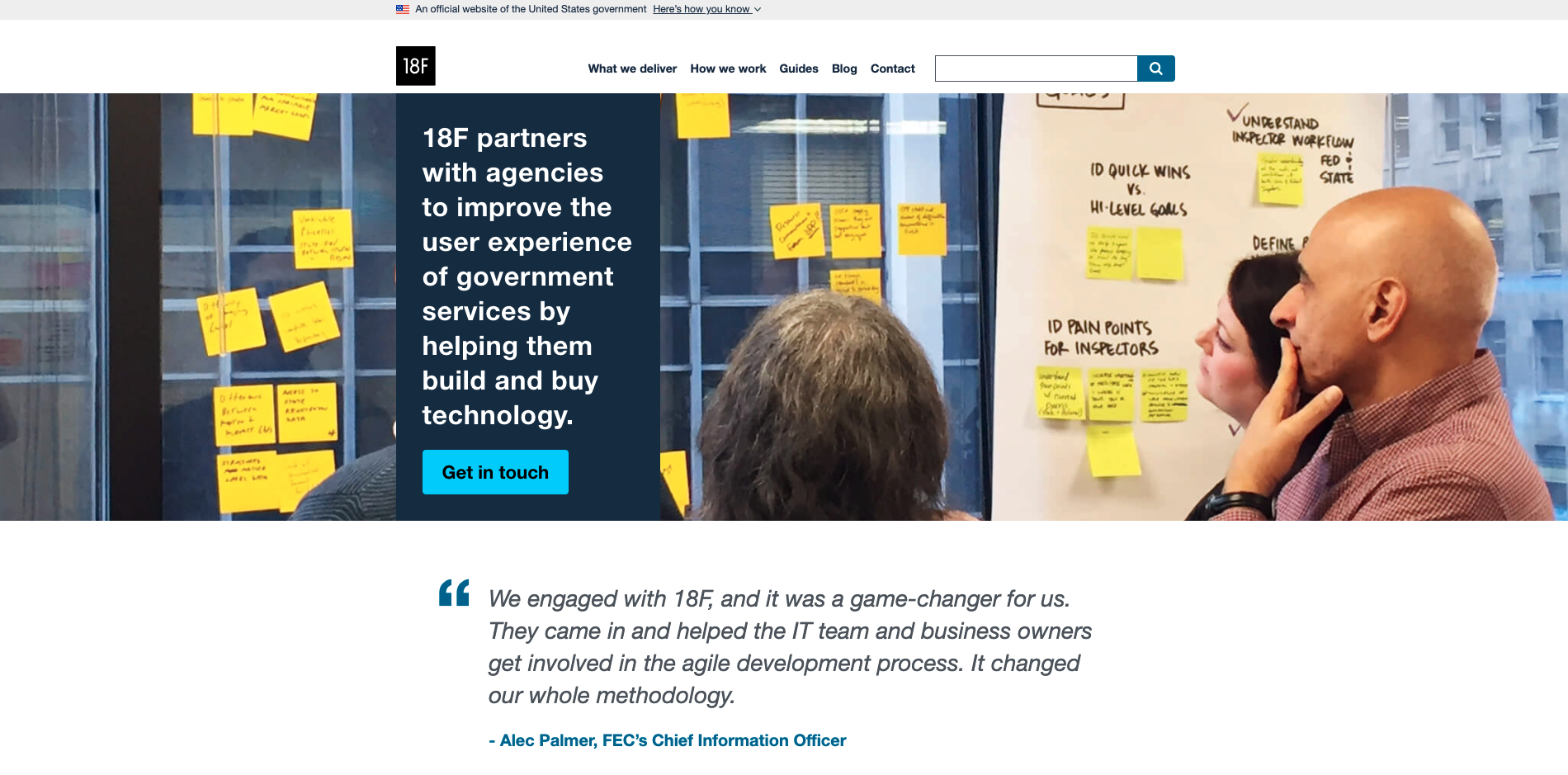

- What this means: A static site sends the same content every time you reload it. The content doesn’t change unless the site owner updates it — for example, by publishing a new page on a blog. In general, all users of the site see the same content. A public agency headquarters website is a classic example: 18f.gsa.gov is a static site!

- Why and when it’s a good choice: Many government agencies just need to publish information to the web. Static sites are generally the simplest kind to build, maintain, and host. They are lower-cost, compared to more complex web architectures. And U.S. federal agencies can use federalist.18f.gov to build, launch, and manage their static sites.

If you can’t make it a static site, it should probably be a server-rendered app.

- What this means: Think of a site where you can log in and see data related to your account. When you reload the page, you’ll see the latest information relevant to you — for example, your orders on a shopping website. This is more complex than a static website, because the data needs to be securely stored and related to each user. A server-rendered app accomplishes this by having a back end server, which talks to a database to fetch the right information on request.

-

Why and when it’s a good choice: Sometimes your user needs will require features like:

- Login system to protect data

- Specific user roles within the app

- Complex logic or data processing

In these cases, we’ve had success with popular, tried-and-true, open-source web frameworks for building server-rendered web apps, such as Django and Ruby on Rails.

These frameworks meet our preference for using stable (but still very much actively maintained) technology over cutting-edge. For example, Ruby on Rails was first released in 2004, and its developers actively publish major updates, with the latest major release in 2019. Django was first released in 2005, and its developers actively publish major updates, with its latest major release also in 2019.

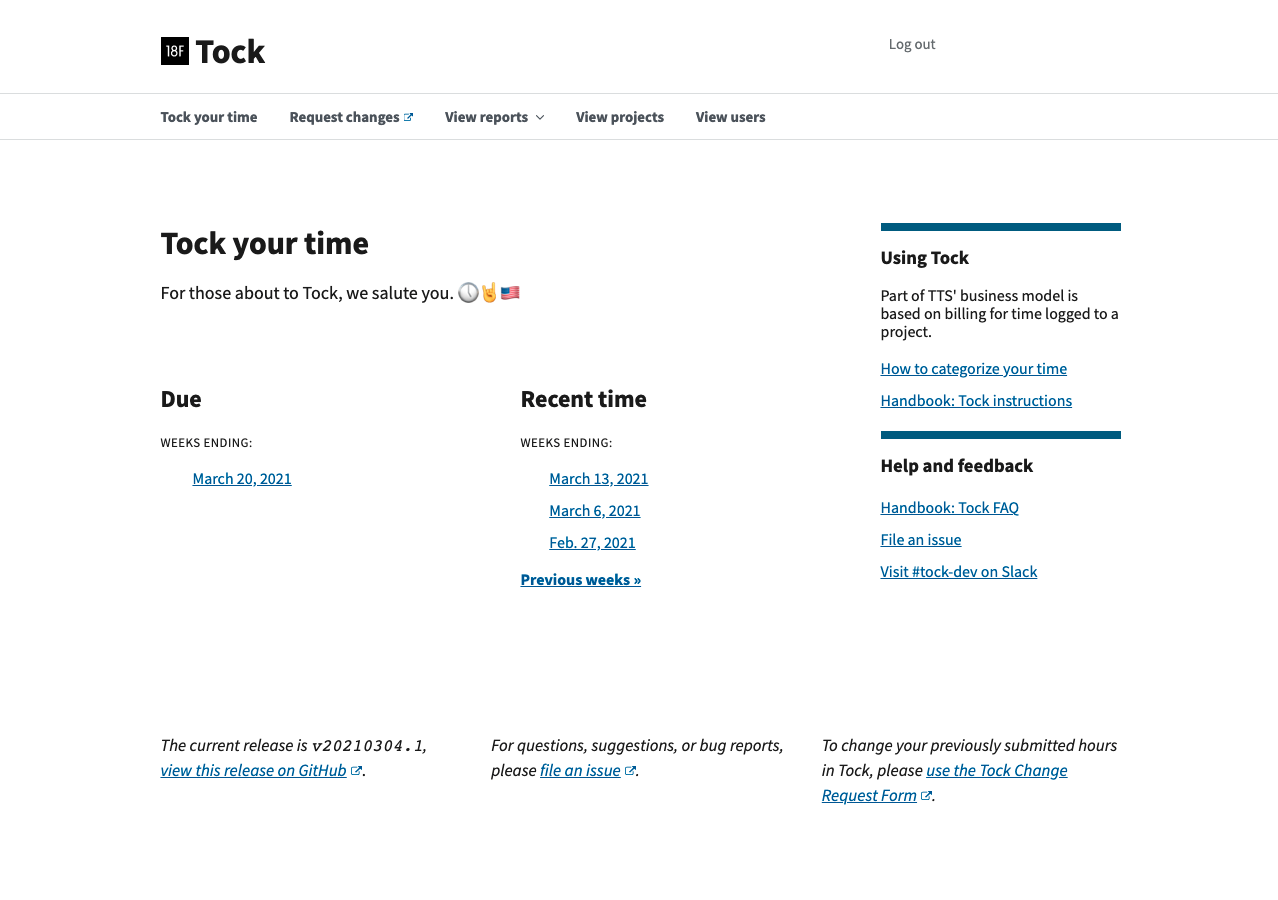

One example of a server-rendered web application is 18F’s internal timekeeping application, Tock. Tock helps 18F team members submit timesheets and manage our time. Each user of the app needs to see different data, and the data needs to be tracked in the database, which makes it a good fit for a server-rendered architecture. Tock has been up and running since 2015. Its simple architecture and use of stable, tried-and-true technology has made it easier to maintain over time. It runs on cloud.gov, a platform that other government agencies can use to run their server-rendered applications, too.

If your use case requires a bit of client-side interactivity, use the above options with a bit of JavaScript.

- What this means: The client side of a web application is the web browser. Your web browser is a powerful thing — it can do things like calculations, animations, and handle user interactions. Client-side interactivity means showing information or handling logic within the web browser itself. Think of a form that gives you helpful hints as soon as you type in valid or invalid data. On the web, these features are built using JavaScript.

- Why and when it’s a good choice: Your team may have ideas for features they can add to improve the user experience using client-side interactivity. These can be added to static sites or to server-rendered apps. Think about a static website that includes a real-time data feed, or a server-rendered app that has a form with interactive hints as the user fills out the form.

You can think about “using just enough JavaScript” to add the required interactivity, without adding unnecessary complexity. This is a good opportunity to ask if new features are being driven by user input and tested with users on an ongoing basis.

If your use case requires complex client-side interactivity, then you may need a single-page application.

- What this means: Just as above, client-side interactivity means handling logic within web browsers. Single Page Applications are specifically designed to do this. If you notice a lot of transitions, animations, and loading spinners on the page, you might be looking at a Single Page App — and if you hear terms like React, React Router, Redux, Angular, Vue.js, or Ember from your web team, depending on the context, you might be hearing about a Single Page App architecture. All of these options use JavaScript in the browser to deliver functionality to users. They often require two sets of applications — one for the client side, and a back end server to deliver and store data over time.

- Why and when it’s a good choice: Single Page Apps involve trade-offs with the very things we need to be wary of as government technologists. Because they often involve multiple layers of technology, they can be more costly to build and harder to maintain. Because they use JavaScript to deliver functionality, it often requires more development work to make a Single Page App accessible. And from a security perspective, Single Page Apps often require checking for things like authorization in two places, the client side and the server. Security in a Single Page Application context can be more complex and require more thought to get right.

The question is: given these trade-offs, how much client-side interactivity do you need?

Single Page Apps can be the right choice when you and your team have weighed these trade-offs, and determined that heavy client-side interactivity is necessary in order to deliver the core features of your app. Some specific situations where Single Page Apps can really shine might be:

- Web applications where offline support is crucial, such as an application designed for workers in the field where internet access might be spotty. Storing data and logic in the browser could be very important in scenarios like these.

- Web applications designed to read from an existing data source — for example, a web application designed to show visualizations or dashboards based on existing datasets.

- A “calculator” application that can use public rules or data to help users calculate the outcomes of different scenarios. If the data needed to run the calculator is public and lightweight, the use case might not need a database or a server at all.

Some may argue that Single Page Apps “feel more modern.” We feel that a modern web application is designed based on user needs, highly accessible, and easy to maintain — whether or not it’s a Single Page App.

What are some questions you can ask your team to move in this direction?

Asking questions is one of a product owner’s most powerful tools when working with their engineers. Below are a few that you can ask when navigating web architecture choices on a project:

- What impact would these different options have on accessibility?

- What impact would these different options have on the user experience?

- What impact would these different options have on security?

- How many different programming languages or skill sets will we need to fix issues in this application?

- How many different programming languages or skill sets will we need to deploy updates to this application?

- Can you show me an example of an application with this technology in our department or agency that has been maintained over several years?

- What if team members are offered new jobs or win the lottery — how easy or difficult will it be to hire developers with skills to fix issues or deploy updates?

We hope that these questions and advice will be useful. Good luck as you push for simplicity and all the benefits that come with it!